Anila Kathi, Mandara Raj J P.

Keywords: Welfare Reform, Direct Benefit Transfers, Public Distribution System, Cash Transfers, Digital Inclusion, Blockchain in Welfare, AI-driven Governance, Poverty Alleviation, Financial Inclusion.

Introduction

The effective delivery of welfare subsidies is a cornerstone of public policy, ensuring socio-economic equity and poverty alleviation. Government expenditure on welfare programs in India is substantial, with $60 billion allocated in 2018–19, primarily through the Public Distribution System (PDS). However, systemic inefficiencies, including misuse and corruption, led to an estimated 40% loss of these funds (Das & Sethi, 2024; Dreze & Khera, 2017). The government introduced Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT) in 2013 for select schemes, such as LPG subsidies, leveraging Aadhaar-based authentication to transfer funds directly to beneficiaries’ bank accounts to address these challenges. While DBT aimed to eliminate intermediaries and improve transparency, its effectiveness has remained on par with PDS due to challenges such as lack of auditability, misallocation of funds, and an over-reliance on underdeveloped rural banking infrastructure (Varshney et al., 2020; Shibu et al., 2020).

Recognizing these limitations, emerging technologies like blockchain present a promising alternative for welfare distribution. Blockchain, with its cryptographic hash-secured distributed ledgers, ensures an immutable record of transactions, fostering transparency and accountability. Smart contracts, integrated with Aadhaar, could automate subsidy disbursements while bypassing traditional banking constraints in rural areas (Sayed Azain Jaffer et al., 2020). This decentralized system would enhance efficiency, prevent leakages, and create an auditable welfare ecosystem, mitigating corruption and financial mismanagement.

India’s welfare framework remains at a critical juncture where technological integration could redefine the effectiveness of policy interventions. This paper analyses how policy design, governance, and innovation can optimize subsidy delivery by evaluating existing welfare models and exploring blockchain-based solutions. The discussion highlights the trade-offs between cash and in-kind transfers, advocating for a hybrid model that harnesses technological advancements and on-ground accessibility to achieve inclusive development (Robeyns, 2006; Alkire & Foster, 2011).

Effectiveness of Welfare Models: Lessons from India and the World

Welfare programs in India, including Cash and In-kind transfers, are vital in addressing poverty (Das et al., 2024). Capability Approach of Amartya Sen provides a solid framework for evaluating these programs (Robeyns, 2006). Sen’s approach advocates for cash transfers, as they address the specific needs of recipients (Jaron, 2011). Nevertheless, the in-kind benefits directly address essential needs like food, healthcare, and education, transforming lives in regions with limited market access or prone to risks of cash misuse (Gadenne, 2021).

Multidimensional poverty highlights the intersecting deprivations that the poor face (Alkire et al., 2011). In India, cash-based programs like PM-KISAN and DBT help families invest in education, healthcare, and housing, addressing multidimensional poverty (Bastalgi et al., 2016). Research indicates that by providing ₹6,000 annually to smallholder farmers, the PM-KISAN scheme increases consumption and reduces reliance on credit, although challenges in accurately identifying and targeting beneficiaries persist (Varshney et al., 2020).

In-kind benefits, like PDS, can be invaluable in tackling specific poverty issues like hunger and malnutrition. Initiatives such as the Midday Meal Program effectively address multiple dimensions of poverty, enhancing child nutrition and increasing school attendance (Neetu et al., 2019). Nonetheless, challenges like mismanagement and poor logistics limit the effectiveness of these programs (Dreze et al., 2017).

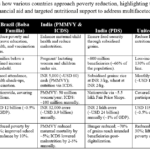

Globally, programs like Brazil’s Bolsa Familia and Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) integrate cash and in-kind assistance. Bolsa Familia, a conditional cash transfer, has reduced poverty for over 36 million people by linking benefits to education and healthcare (Soares et al., 2010). The PSNP integrates food aid, cash transfers, and public work programs to improve food security and resilience among rural populations, particularly during droughts (Wheeler et al., 2011).

Comparative Analysis of Key Poverty Alleviation Programs

A 2009 UNDP (India) discussion paper highlights the high efficiency of conditional cash transfer (CCT) programs, such as Brazil’s Bolsa Familia, in poverty reduction, emphasizing their targeting and impact (Ministry of Development and Social Assistance, Family and Fight against Hunger, Brazil, 2024). Despite systemic inefficiencies, India’s PDS, PMMVY, and ICDS programs have effectively reduced poverty.

A 2009 UNDP report suggests exploring the implementation of CCT programs as a potential solution to the inefficiencies and limited effectiveness of existing programs. Dr. Himanshu et al. (2013) emphasize the need for technological integration (DBT) and reform of the existing PDS, including integrating cash transfers at the point of delivery, to enhance the overall impact of welfare programs in India.

Role of Technology and Innovation in Enhancing Welfare Program Delivery

Advanced information and communication technologies have emerged to mitigate limitations (Kalla et al., 2023) of government-to-people social transfer programs (Gelb et al., 2020). However, the digital cash assistance transition depends on factors such as robust infrastructure, beneficiary readiness, organizational capacity, and a supportive regulatory environment (Kalla et al., 2023).

India’s JAM trinity (Jan Dhan Yojana, Aadhaar, and Mobile connectivity) plays a game-changer in streamlining welfare distribution. The three modes of identification concern direct subsidy transfer. They enable direct benefit transfer, eliminate intermediaries, and reduce leakages (Gosh, 2017).

Globally, the drive toward systematically adopting effective and accountable technological solutions in providing welfare programs has led to the exploration of various delivery mechanisms (Smith et al., 2011).

Electronic Payment Systems for Welfare Program Delivery: –

- Pre-paid Debit Cards offer a secure and convenient method of delivering welfare benefits. For instance, South Africa’s SASSA card distributes social grants like pensions, disability, and child support. In contrast, Australia’s Cashless debit card aims to address specific welfare challenges by restricting spending on alcohol and gambling in vulnerable communities. Nevertheless, both initiatives highlight the potential of digital financial inclusion in social welfare systems (Luke et al., 2018).

- Smart Cards: – This streamlines welfare, acting as secure digital IDs for beneficiaries, tracking payments, and preventing fraud. For example, India’s NREGS uses smart cards to streamline wage payments (Muralidharan., 2017), while Mexico’s Prospera program aims to provide conditional cash transfers to low-income families (Bold et al., 2012).

- Mobile Money Transfers: Mobile money transfer systems transfer welfare funds directly to recipients’ accounts. Kenya’s M-Pesa allows direct cash transfers to mobile wallets. Similarly, India’s Direct Benefit Transfer uses Aadhaar-linked accounts to deliver subsidies directly to beneficiaries. These models revolutionize welfare, creating efficient, inclusive, and accountable systems (Yadhav et al., 2024).

- Mobile Payments with Vouchers via SMS: These vouchers deliver pre-funded digital payments directly to recipients for specific goods or services. To illustrate, India’s e-RUPI vouchers, delivered via SMS or QR code, are used for programs like Ayushman Bharat and Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana. Kenya’s SANERGY toilet voucher scheme provides access to hygienic sanitation facilities (Dhokad et al., 2021).

Since their introduction, cash and in-kind transfers have faced significant challenges worldwide. Technology and innovations address challenges such as leakages and corruption, program mismanagement, and errors in beneficiary targeting (Shibu et al., 2020). Programs such as Brazil’s Bolsa Familia, South Africa’s SASSA card, and Kenya’s M-Pesa have reduced inefficiencies.

As per Glenbrook (2020) and Gelb et al. (2020), the potential for over 60 million new accounts across six countries revealed a significant expansion of financial inclusion through digital payments. According to the study of Smith et al. (2011), e-payment systems have proved accessible to recipients of welfare programs. These have increased convenience, user-friendliness, and legal accessibility (Smith et al., 2011).

These e-payment systems benefit governments and recipients (Klapper et al., 2017). As stated by Klapper et al., 2017, the benefits include lowering government costs by reducing administrative costs, lowering disbursement costs, and minimizing unauthorized payments. According to their research, recipients’ costs are lowered by reducing travel time and expenses and shorter wait times. According to Klapper and Singer’s research, the other benefits include improved speed and timely delivery through instantaneous transfers, increased transparency and reduced leakage, increased security and lower crime, increased financial inclusion, and increased women’s economic empowerment.

Despite ICT’s transformative potential in welfare delivery, several challenges hinder its universal adoption. The barriers include the digital divide, the failure of biometric systems, and the exclusion of vulnerable groups like older people and tribals due to digital literacy. Smith et al. (2011) provide a few more barriers, such as the high cost of technology, lack of grievance redressal mechanisms, and language barriers.

Addressing the above challenges requires a multi-pronged strategy. All stakeholders should work together to improve technological advancements, and the capacity of stakeholders to use new technology should also be developed (Smith et al., 2011). Incorporating emerging technologies such as AI, blockchain, and ML will transform the welfare distribution mechanisms. The multifaceted strategy includes better infrastructure, robust cybersecurity policies, multilingual digital platforms, and capacity-building initiatives for officials and beneficiaries.

Additional Insights

The future of welfare governance lies in leveraging artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and digital financial inclusion to create a more responsive and adaptive social security system. Traditional welfare models operate on fixed eligibility criteria, often failing to account for dynamic socio-economic changes such as sudden job loss, inflation, or climate-induced displacement. AI-driven predictive analytics can revolutionise welfare distribution by identifying at-risk populations in real time, forecasting poverty trends, and ensuring timely intervention (Kalla et al., 2023). Machine learning models trained on demographic, financial, and behavioural data could refine beneficiary targeting, reducing exclusion errors while ensuring efficient resource allocation.

Additionally, blockchain-based governance could address long-standing concerns of mismanagement and fraud in welfare delivery. Unlike centralized systems vulnerable to manipulation, a decentralized ledger ensures tamper-proof transaction records, enabling real-time monitoring of subsidy disbursements (Sayed Azain Jaffer et al., 2020). Smart contracts could enforce conditional assistance—for example, automatically releasing educational stipends only if school attendance requirements are met. This innovation would minimize bureaucratic delays, prevent fund diversion, and strengthen accountability in social welfare programs.

Furthermore, digital financial inclusion can enhance last-mile welfare delivery by introducing alternative banking solutions for rural beneficiaries. Decentralized finance (DeFi) platforms, mobile wallets, and biometric-enabled e-vouchers could replace traditional subsidy transfers, reducing dependency on banks and empowering beneficiaries with instant access to aid, even in unbanked regions (Yadav et al., 2024). By integrating AI, blockchain, and digital finance, India can transition from a reactive welfare approach to a proactive, data-driven social security system, ensuring policy implementation resilience, efficiency, and equity.

Conclusion

The evolution of welfare models in India highlights the dynamic interplay between policy design, economic realities, and technological advancements. While cash transfers provide financial autonomy, in-kind benefits ensure direct access to essential goods and services. Each model has its strengths and weaknesses, necessitating a nuanced approach that combines both strategies. Technological innovations, such as Aadhaar-linked DBTs, smart cards, and mobile banking, have significantly improved welfare efficiency, yet systemic challenges, such as exclusion errors and digital illiteracy, persist.

India must focus on refining its welfare ecosystem through policy integration, enhanced governance, and digital inclusivity. A hybrid model that tailors welfare assistance to specific community needs backed by robust data analytics and real-time monitoring can pave the way for more effective and equitable social security mechanisms. By drawing lessons from global best practices and continuously innovating, India can build a welfare framework that is both resilient and inclusive, ensuring sustainable poverty alleviation and social equity.

References:

Abelson, J. (2011). A philosophical framework for conditional cash transfers. Social Policy & Society, 10(4), 487–498.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 476–487.

Bantock, L. (2018). Cashless welfare payments and everyday life: A study of South Africa and Australia (Doctoral dissertation). University of Warwick.

Bastalgi, F., Hagen-Zanker, J., & Harman, L. (2016). Cash transfers: What does the evidence say? Overseas Development Institute.

Bold, C., Porteous, D., & Rotman, S. (2012). Social cash transfers and financial inclusion: Evidence from four countries. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series.

Das, A., & Sethi, N. (2024). Cash and in-kind transfers in India: Contexts, preferences, and evidence. International Journal of Social Economics.

Dhokad, P., & Singh, V. (2021). Leveraging digital vouchers for public service delivery: e-RUPI. Journal of Digital Innovation, 5(2), 112–126.

Dreze, J., & Khera, R. (2017). Understanding leakages in the public distribution system. Economic and Political Weekly, 52(7), 20–24.

Gelb, A., & Mukherjee, A. (2020). Digital technology in social assistance transfers for COVID-19 relief: Lessons from selected cases. Center for Global Development Working Paper.

Gadenne, L., Norris, S., Singhal, M., & Sukhtankar, S. (2021). In-kind transfers as insurance. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper.

Gosh, S. (2017). Financial inclusion, biometric identification, and mobile: Unlocking the JAM trinity. International Journal of Development Issues, 16(2), 190–213.

Himanshu, H., & Sen, A. (2013). Cash vs in-kind: Examining the efficacy of welfare transfers in India. Yojana, 57(3), 23–27.

Ingrid, R. (2006). The capability approach in practice. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 14(3), 351–376.

Juntunen, E. A., Kalla, C., Widera, A., & Hellingrath, B. (2023). Digitalisation potentials and limitations of cash-based assistance. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 97, 104005.

Muralidharan, K., Niehaus, P., & Sukhtankar, S. (2017). Smartcards in public services: Improving efficiency and reducing leakages. Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL).

Neetu, A. G., & McKay, F. H. (2019). The public distribution system and food security in India. Journal of Food Security, 10(4), 112–125.

Ministry of Development and Social Assistance, Family, and Fight Against Hunger. (2024). Bolsa Família reduces inequalities in Brazil, according to IBGE’s Continuous PNAD. Retrieved from Ministry of Development and Social Assistance, Family and Fight Against Hunger.

Sabates-Wheeler, R., & Devereux, S. (2011). Working Paper No. 4: Cash transfers and high food prices—Explaining outcomes on Ethiopia’s productive safety net programme. Institute of Development Studies Working Paper Series.

Shibu, M. E., Joseph, D. R., & Kunjumon, N. (2020). Impact of digitalisation on the public distribution system in achieving the United Nation’s sustainable development goal of zero hunger. International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT), 8(6), 145–159.

Smith, G., MacAuslan, I., Butters, S., & Tromme, M. (2011). New technology enhancing humanitarian cash and voucher programming. CaLP Research Report.

Soares, F. V., Ribas, R. P., & Osório, R. G. (2010). Evaluating the impact of Brazil’s Bolsa Família: Cash transfer programs in comparative perspective. International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth Working Paper.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), India. (2009). Discussion paper: Conditional cash transfer schemes for alleviating human poverty—Relevance for India.

Varshney, D., Joshi, P. K., Roy, D., & Kumar, A. (2020). PM-KISAN and the adoption of modern agricultural technologies. Economic and Political Weekly, 55(23), 48–55.

Yadav, O. P., Teotia, R. K., Choudhary, D., & Kumar, R. (2024). Digital marketing ethics and financial inclusion: Balancing profitability with social responsibility. In Digital Economy of India: Recent Developments and Emerging Perspectives.