Anila Kathi, Mandara Raj J P

Introduction

Poverty in India is a multidimensional issue deeply influenced by economic, social, and political factors. Shukla (n.d.) identifies key drivers of poverty, including low education levels, inadequate access to healthcare, and persistent gender inequality. These factors often result in a cycle of deprivation, manifesting in issues like malnutrition, substandard housing, and lack of access to essential services, all of which exacerbate the conditions of poverty in India.

Recent studies have highlighted that poverty has steadily declined in India over the years, though the pace and extent of the reduction have varied. Panagariya and Mukim (2013) show that from fiscal years 2004-2005 to 2009-2010, accelerated growth led to a significant decrease in poverty rates. Notably, the decline in poverty was more pronounced among socially disadvantaged groups, contributing to a narrowing of the poverty gap between these groups and the more privileged upper-caste populations. This emphasizes the importance of inclusive economic growth policies aimed at uplifting marginalized sections of society.

Further, the role of food subsidies in alleviating poverty is underscored by Bhalla, Bhasin, and Virmani (2022), who provide estimates of extreme poverty in India, showing that food transfers have played a crucial role in ensuring low levels of extreme poverty, even during the pandemic. In 2019, extreme poverty stood at a mere 0.8%, and food subsidies helped maintain this low level during the crisis year of 2020. The reduction in inequality, as measured by post-subsidy consumption inequality, further reflects the positive impact of food security interventions.

In a more comprehensive and data-driven approach, Kulkarni, Das, Srivastava, and Chakraborty (2023) argue that poverty in rural India is not uniform and is influenced by spatial, social, and economic variables. They advocate for using artificial intelligence and satellite data to understand the complexities of poverty across districts better. Their study identifies regions that are “lagging” in development and calls for focused interventions in these areas to address the specific needs of vulnerable populations.

Hence, poverty in India remains a deeply entrenched issue, but economic growth, targeted social policies, and technological advancements in data collection and analysis offer promising solutions. A multifaceted approach, informed by traditional and modern methods, is crucial for addressing India’s complex and evolving nature of poverty.

Poverty in India is a complex and evolving issue, influenced by various socio-economic factors and shifting definitions. This article explores two main themes: the changing nature of poverty and its status before, during, and after the pandemic. The first theme examines how poverty has been historically defined and measured, from colonial-era subsistence-based models to modern approaches encompassing factors like education, healthcare, and living standards. It emphasizes the need for a broader, multidimensional understanding of poverty beyond just income-based measures. The second theme delves into recent poverty trends, focusing on the pre-pandemic period, the disruptions caused by COVID-19, and the post-pandemic recovery. It highlights the impact of government welfare initiatives, such as food transfers and social protection schemes, in mitigating the effects of the pandemic, especially in rural areas. The article concludes by stressing the importance of adopting comprehensive, inclusive policies to address poverty in all its forms, ensuring that vulnerable populations are not left behind.

Divergent Definitions of Poverty and Their Implications

Poverty in India has evolved as a concept, reflecting changing human needs (Goulden et al., 2014) and its multidimensional. Definitions of poverty encompass terms like subsistence, protection, and participation, with Dadabai Naoroji introducing a “Poverty Line” based on subsistence needs, defined as the “necessities of a human to live an ordinary life with good health and decency” (Hashim, 2016). However, Naoroji’s definition excluded essential needs like healthcare, education, and transportation (Narayan et al., 2023). The Rowntree Study (1901), one of the colonial surveys, measured poverty through calorie intake but overlooked socio-economic inequalities (Pomati et al., 2024).

In the 1970s, the Planning Commission of India established a poverty line based on calorie intake—2,400 calories (rural) and 2,100 calories (urban) (Seema et al., 2020). This method, however, was criticized for ignoring non-caloric needs (Alok, 2020). The World Bank defines extreme poverty as living on less than $2.15 daily, providing a global comparison standard (Anker, 2006).

Divergent definitions can lead to mismatches in welfare targeting, leaving vulnerable populations underserved (Sumit et al., 2011). Income-based measures may overlook hidden poverty, particularly in urban and migrant populations (Stephens, 2012). Harmonizing income-based and multidimensional metrics is essential (Stephens, 2012). Leveraging technology (Big data and AI) can improve poverty measurement and refine policies (Christopher, 2017).

Status of Poverty: Pre-pandemic, post-pandemic, and recent trends

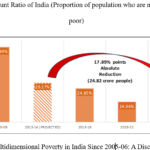

India’s poverty trends have undergone significant shifts since 2000. Adopting the MMRP (Modified Mixed Recall Period) method in 1999-2000 improved poverty estimation accuracy (Bhalla et al., 2022). Between 2004 and 2020, India experienced a consistent decline in poverty, marked by significant reductions at PPP thresholds of $1.9 and $3.2 per day (Bhalla et al., 2022). This decline was driven by economic growth, inflation trends, and effective welfare programs like MGNREGA, rural electrification, and infrastructure development (Bhalla et al., 2022).

The pandemic (2020-2021) disrupted these declining trends, increasing extreme poverty worldwide for those below $1.9 PPP per day (Bhalla et al., 2022). To address this, the government implemented various welfare measures (Bhalla et al., 2022), including expanded food transfers through PDS, DBT, and the extension of MGNREGA to mitigate the pandemic’s economic impact (Arbatli et al., 2023).

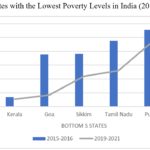

Figures 1 and 2 show that Bihar and Jharkhand consistently ranked among the poorest states in 2015-2016 and 2019-2021. The northern and eastern states exhibit higher poverty levels compared to southern states.

Post-pandemic poverty trends were uneven between rural and urban India. During the pandemic, mass migration from urban to rural regions highlighted the resilience of the agricultural sector, which helped reduce rural poverty (Hagera et al., 2021). In contrast, metropolitan areas faced heightened unemployment and inflation (Vedika et al., 2021). Targeted interventions, such as free food distribution under PMGKAY, were pivotal in cushioning the impact (Economic Survey 2023-2024).

According to SBI Research (2024-2025), the Consumption Expenditure Survey shows a notable decline in poverty. Rural poverty dropped to 4.86% in FY24 (from 7.2% in FY23 and 25.7% in FY12), while urban poverty fell to 4.09% (4.6% in FY23 and 13.7% in FY12). The SBI report attributes this reduction to improvements in physical infrastructure, which have helped bring poverty levels below 5%.

Multidimensional Perspectives on Poverty

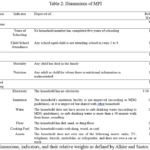

Poverty goes beyond income deprivation; it is the lack of essential capabilities needed for a dignified life (MPPN, n.d.). Global organizations acknowledge his multidimensional aspect of poverty, as reflected in the Sustainable Development Goal to “End poverty in all its forms, everywhere” (UN, n.d.). Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach (Sen, 1992) popularized this perspective, later institutionalized through the UNDP’s Multidimensional Poverty Index, which focuses on education, health, and living standards (Alkire & Santos, 2010).

Bourguignon et al. (2003) emphasized that poverty should be measured through income and non-income indicators, which capture welfare aspects beyond income (Ravallion,1996). Kakwani and Pernia (2000) further highlighted this approach, defining pro-poor growth as ensuring no one is deprived of essential capabilities.

This methodology, formulated by Alkire and Santos, was used by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative in collaboration with the United Nations Development Programme to develop the global Multidimensional Poverty Index (Alkire & Santos, 2014) and is also adopted by NITI Aayog.

A natural question in the scientific community is whether growth impacts multidimensional poverty differently than income poverty (Santos et al., 2017). Kakwani (2000) noted that incorporating all relevant capabilities into pro-poor growth measurement is challenging. Based on the estimations made (Santos et al., 2017), using cross-section regressions, it is concluded that “economic growth has a greater and more significant impact on income poverty than on multidimensional poverty.”

Poverty is a complex phenomenon influenced by various interrelated factors (Zulkifli et al., 2023). Multidimensional approaches highlight this complexity and underscore the limitations of relying solely on income-based measures.

Additional Insights

Migrants, particularly from rural to urban areas, often face a form of hidden poverty that goes beyond income measurements. This poverty is influenced by displacement, lack of stable employment, and absence of social security. Despite earning above the poverty line, they may still struggle due to limited access to healthcare, education, and housing. For instance, migrant workers in cities often live in informal settlements with inadequate access to sanitation despite earning an income above the $2.15 threshold, reflecting a more complex, multidimensional poverty.

Digital literacy is increasingly vital in reducing poverty, especially in rural areas. Access to online education, job opportunities, and government services can empower individuals, breaking the cycle of poverty. An example can be seen in rural India, where initiatives like Digital India have enhanced access to financial inclusion and online healthcare services, reducing poverty by providing marginalized groups with tools for self-sufficiency.

Conclusion

In conclusion, India’s evolving concept of poverty highlights the need for a more nuanced, multidimensional approach to its measurement and intervention. From the colonial era, which focused on subsistence needs, to the contemporary emphasis on capabilities, poverty must be viewed through various lenses, including health, education, and access to essential services. The shift from a calorie-based definition of poverty to income-based thresholds, as defined by the World Bank, and the adoption of multidimensional poverty indicators such as the MPI underscores the growing recognition that poverty extends beyond mere income deficits.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the progress made in poverty reduction, particularly in rural areas. However, the resilience of the agricultural sector and government interventions such as food transfers and social protection schemes helped mitigate the adverse effects. Post-pandemic poverty trends have shown uneven patterns across rural and urban India, highlighting the persistent challenges in addressing hidden poverty in urban migrant populations.

Addressing poverty in India requires a holistic approach that harmonizes income-based and multidimensional metrics, ensuring that welfare policies target economic relief and the broader capabilities essential for a dignified life. Leveraging technological advancements, such as big data and AI, can play a pivotal role in refining poverty measurement and ensuring more efficient and inclusive policy implementation. Future actions should focus on improving data accuracy, expanding access to quality education and healthcare, and ensuring sustainable economic growth that benefits all sectors of society. Emphasizing equitable development will be crucial in meeting the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal of ending poverty in all its forms, everywhere.

References

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2014). Measuring acute poverty in the developing world: Robustness and scope of the multidimensional poverty index. World Development, 52, 71–91.

Anker, R. (2006). Poverty lines around the world: A new methodology and internationally comparable estimates.

Alok, A. (2020). The problem of poverty in India. International Journal of Research and Review, 2(5), 39423–39426.

Arbatli-Saxegaard, E., Coppo, M., Khalil, N., Kotera, S., & Unsal, D. F. (2023). Inequality and poverty in India: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and policy response.

Bhalla, S. S., Bhasin, K., & Virmani, A. (2022). Pandemic, poverty, and inequality: Evidence from India.

D’Arcy, C., & Goulden, C. (2014). Anti-poverty strategies for the UK.

Dilnashin, H., Birla, H., Rajput, V. D., Keswani, C., Singh, S. P., Minkina, T. M., & Mandzhieva, S. S. (2021). Economic shock and agri-sector: Post-COVID-19 scenario in India.

Doyal, L., & Gough, I. (1991). A theory of human need.

The Economic Survey (ES) 2023-2024.

Gaur, S., & Rao, N. S. (2020). Poverty measurement in India: A status update.

Gupta, V., Santosh, K. C., Arora, R., Ciano, T., Kalid, K. S., Mohan, S., & Shafee, K. (2021). Socioeconomic impact due to COVID-19: An empirical assessment.

Hashim, S. R. (2016). “Further reflections on counting the poor – particularly regarding identifying the urban poor,” Centre for Economic and Social Studies, Hyderabad.

Kakwani, N., & Pernia, E. M. (2000). “What is pro-poor growth?” Asian Development Review.

Kulkarni, A., Das, R., Srivastava, R. S., & Chakraborty, T. (2023). Learning and reasoning multifaceted and longitudinal data for poverty estimates and livelihood capabilities of lagged regions in rural India.

Mazumdar, S., & Sharma, A. N. (2011). “Poverty and social protection in urban India: Targeting efficiency and poverty impacts of the targeted public distribution system.”

Multidimensional Poverty Peer Network (MPPN). (n.d.), “What is multidimensional poverty?”.

Narayan, L., & Singh, S. (2023). “Economic thoughts of Dadabhai Naoroji (With special reference to the theory of drain).”

Njuguna, C., & McSharry, P. (2017). “Constructing spatiotemporal poverty indices from big data.”

Pomati, M., Nandy, S., Jose, S., & Reddy, B. (2024). “Multidimensional adult and child poverty in India—Establishing consensus about socially perceived necessities for a new measure of poverty.”

Ravallion, M. (1996). “Issues in measuring and modeling poverty,” Economic Journal, 106(439), 1328–1343.

Roy, T. (2007). “Globalization, factor prices, and poverty in colonial India,” London School of Economics and Political Science.

Santos, M. E., Dabus, C., & Delbianco, F. (2017). “Growth and poverty revisited from a multidimensional perspective.”

SBI report (2024-2025), p.g.2.

Sen, A. (1992). “Inequality re-examined. Clarendon Press”.

Shukla, S. (n.d.). Exploring the causes and effects of poverty in India: A comprehensive analysis. Piedmont Virginia Community College.

Srinivasan, T. N. (2007). “Poverty lines’ in India: Reflections after the Patna Conference.” Economic and Political Weekly.

Stephens, C. (2012). “Urban inequities; urban rights: A conceptual analysis and review of impacts on children, and policies to address them.”

United Nations (UN). (n.d.). Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere. Retrieved August 11, 2022, from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/poverty/

Zulkifli, F., & Zainal Abidin, R. (2023). “The multi-dimensional nature of poverty: A review of contemporary research.”