Evolving Terror Financing Methods: Traditional and Modern Aspects

Muskaan Grover, Richa Sharma and Vivek Jha

Terrorist organizations have been consistently evolving their terror financing pathways to support their functional needs, and to protect themselves from counter-terrorism measures. This article delves into the intricate mechanisms used by terrorist organizations, ranging from traditional fundraising methods such as state sponsorships, charities, and informal financial systems, to upcoming technological innovations like cryptocurrencies. It discusses both the challenges posed by these approaches and the global efforts to combat them.

Understanding Terrorist’s Utilisation Of Funds

The process entailing the accumulation of funds by terrorists is referred to as terrorist financing (A. Burgess et al, 2024). These funds are used by terrorist organizations for two major purposes; operational expenditure and organizational expenditure (Norton & Chadderton, 2016).

Funds for planning, preparing, and executing terrorist attacks are categorized as operational expenditures. Terrorist organizations use this money to buy weapons and explosives, pay for transport, and obtain false travel and legal documents to obscure their identity from authorities. While attacks by lone actors and small cells require limited funds; greater amounts are needed to execute complex, grand attacks (Norton & Chadderton, 2016).

Money to fund basic living expenditures like food and accommodation is categorized under organizational expenditure. To recruit and retain members, some terrorist groups also pay regular salaries. Funds used towards building a brand to spread political views on one hand and ensure protection from authorities on the other also come under this category (Norton & Chadderton, 2016).

Terrorist financing is known to be a consequential contributor to geopolitical risks, regional instability, impaired economic development, and instability of financial markets in regions under attack (A. Burgess et al, 2024). Just like businesses and governments, terrorist organizations also seek multiple avenues for revenue sources to maintain cash flow and maximize their revenues (Norton & Chadderton, 2016).

Traditional Fundraising Methods

The traditional methods of fundraising encompass sponsorships, private donations, charities, and non-profit organizations. While terrorists are known to raise funds through illicit networks (A. Burgess et al, 2024) they also rely on legitimate sources such as business incomes, loans, and savings. The four terrorists involved in the 2005 London bombings, for example, funded the attack themselves through their employment salaries, savings, credit cards, and personal loans (Norton & Chadderton, 2016).

Charities and Non-Profit Organisations

Charities and NGOs have been prominent in the terrorist financing arena. For terrorists and their supporters charities and humanitarian organizations are alluring front organizations and therefore charities are prone to being abused by terrorists. While some charities are founded with the interest of financing terror, others are infiltrated and co-opted by terror operatives from within (Jacobson, 2010). There are times when funds raised for legitimate causes are retrieved by terrorists because the contributors do not possess knowledge of where their contributions are being used (Normark and Ranstorp, 2015). In one of the cases, staff at a Saudi-based charity al-Harmain Islamic Foundation, siphoned funds to Al-Qaeda before 9/11 (Norton & Chadderton, 2016).

Non-profit organizations also run on false identities. Individuals claim to be associated with a charity that sends the funds to a sham charitable organization acting as a front for a terrorist group (Norton & Chadderton, 2016). In one of the cases, the leader of a Texas-based charity, Holy Land Foundation was convicted in 2008 for being a Hamas supporter. The foundation on their website claimed their mission was to alleviate suffering through ‘humanitarian programs’ helping ‘disadvantaged, disinherited and displaced people suffering from manmade and natural disasters’ (Jacobson, 2010).

Sponsorship and Donations

When a group’s actions align with a state’s political and ideological interests; states sponsor terrorist organizations. State sponsorship happens in multiple forms such as the supply of weapons, provision of false identity documents, safe havens and passages, money transfers, et al. Since the 1980s Iran has been known to be an active sponsor of terrorism by providing weaponry and financial support to groups such as Hezbollah, Hamas, and Shia militants. State sponsorship was also a major source of funding for terrorist organizations during the Cold War (Norton & Chadderton, 2016).

Diaspora and groups centered on ethnicity, religious domination, and sects that coincide with that of the terrorist organization donate funds in personal interest (Norton & Chadderton, 2016). Tajheez Al-Ghazi that is, ‘preparation’ (tajheez) and ‘warrior’ (al-ghazi), is a common method of Islamic individual contribution. For individuals who do not participate in jihad physically, sponsorship allows them the honor of contributing in proxy. Funds can be through humanitarian channels or as easy as buying someone an airline ticket (Normark & Ranstorp, 2015). Before 9/11 Al-Qaeda raised $30 million a year through donations from sympathetic individuals and organizations (Norton & Chadderton, 2016).

Illicit Networks

Terrorist groups are drawn towards illicit activities to raise funds because they help quickly generate larger amounts. These activities range from low-level theft and fraud to higher organized crimes and trade (Norton & Chadderton, 2016). Securing a car loan or leasing options with no intention of paying back the loan is a common practice. Extensive connections have also been made between trade in counterfeit goods and terrorist organizations like Al-Qaeda. Terrorist groups operate and make profits in the global counterfeit markets which are valued as a $500 billion yearly industry (Normark & Ranstorp, 2015).

How Terrorists Move The Money

Understanding the movement of the money raised is crucial. Terrorists often raise money in a place that is different from where they are located and different from the place of attacks. Moving funds from their place of origin to operational areas where they are to be utilized is essential for terrorist groups to be effective (Freeman & Ruehsen, 2013).

Cash Couriers

Cash is concealed in luggage, vehicles, packages, or anything that can hold volumes of it while moving it across international borders. In case of uncontrolled borders, the efforts to conceal the cash are not undertaken. In the 1990s and before the 9/11 attacks, Al-Qaeda used to rely on cash couriers. While using cash couriers security and speed are important considerations. Not only are trusted personnel needed to move the money, but the process is much slower than electronic means (Freeman & Ruehsen, 2013).

Informal Transfer System

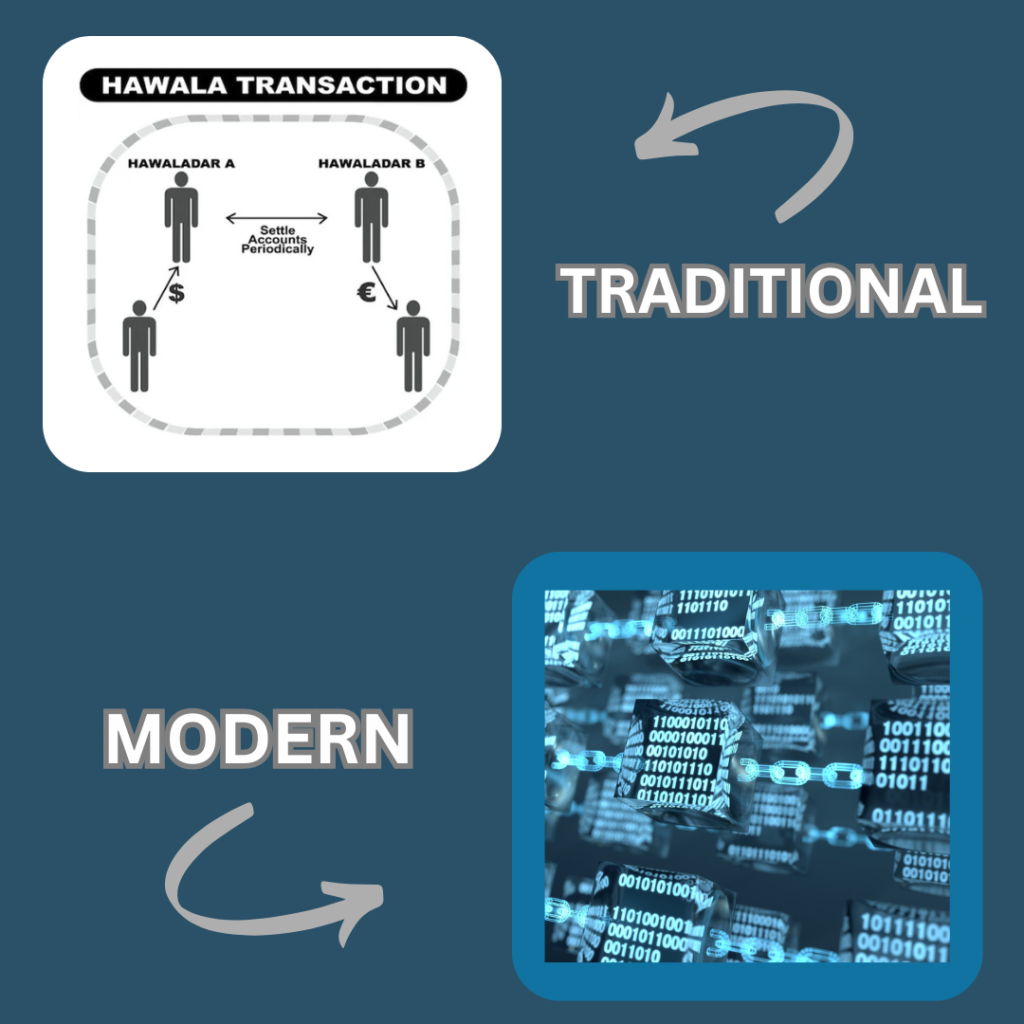

Informal financial networks have different names across places, Hawala/Hundi in South Asia, Fei Chi’en in China, Phoe Khan in Thailand, and Door to Door in the Philippines. Traditional roots and ethnic ties influence these networks which operate in areas where large ethnic diaspora live and the financial banking sector is not well established. These networks are estimated to be a part of the US $500 global remittance system. While many countries have legalized the hawala system, most dealers continue to operate illegally due to high license and registration fees. In the Middle East and South Asia, hawala networks operate in the following way; a worker in Dubai who wants to send US $1000 to his wife in Pakistan contacts a hawaladar and gives him the funds. That hawaladar then connects with a fellow hawaladar in Pakistan. The hawaldar in Dubai shares a code, with the worker and the hawaladar, in Pakistan. The worker’s wife then connects with the hawaladar in Pakistan, shares the code, and receives the funds minus a commission. In this process, no actual movement of funds takes place across borders. Hawala and other informal transfer systems are fast with transactions happening within hours (Freeman & Ruehsen, 2013).

Money Service Businesses

Money remittance and currency exchange providers get exploited for money laundering and terrorist finance purposes (Normark and Ranstorp, 2015). Like banks money service businesses are governed by the same laws and regulations but do not follow the rigorous ‘know your customers’ (KYC) procedures, they also do not require the customers to have an existing account with them for transactions, only valid IDs are needed. MSBs transfer funds quickly, with low risks of detection, and hence are easy to manipulate for financing terror (Freeman & Ruehsen, 2013).

Cryptocurrencies as a new method of terror financing

For terror funding, the most significant property of any financial communication channel has been its adaptability and its resilience to the technology used by the authorities. Mechanisms like hawala and cash couriers act as prominent financing methods for terror groups but due to their inherent limitations and increased surveillance tied up with modern counter-terrorism technologies along with frameworks like anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorism financing (CTF) (FATF, 2021), the coverage and extent of their impact have been controlled significantly. This has driven terrorists to shift to digital and more sophisticated financial channels, in particular cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency and the rise of blockchain have opened new avenues of financing for terrorist groups. For instance, after the increased surveillance post-2015, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) was forced to shift to bitcoins for its operations as its Hawala networks took a significant hit. Encrypted forums were used to distribute the manuals to the donors on how to use Bitcoin wallets (Chainalysis, 2020).

Cryptocurrencies which are often referred to as ‘virtual currency’ have emerged as a new source of terror financing because of their attractive characteristics such as anonymity, global reach, speed, ease of use, non-repudiation, and low cost usage. Cryptocurrencies have been made using two major methods. First, the creator decides the number of units of the currency that will ever be needed and then creates all the currencies at once, further releasing them according to a schedule. Second, people create the currency over time, but the maximum units of the same are fixed in advance (Brill & Keene, 2013).

Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are created or mined by solving extremely difficult mathematical algorithms. They can also be purchased from a Bitcoin exchanger, who exchanges conventional currencies for Bitcoins based on the fluctuating exchange rate. Bitcoins are then stored in a digital wallet with the user’s Bitcoin address. For conducting a transaction only the Bitcoin address of the user is sufficient and the transaction is recorded in a public ledger called the ‘Blockchain’ that makes it anonymous.

Unlike traditional methods where money is supposed to be moved physically across borders, cryptocurrencies allow instant settlement and anonymous transactions without the need for middlemen (Dion-Schwarz, Manheim, & Johnston, 2019). In 2020, security agencies discovered several bitcoin transactions linked to Al-Qaeda and their operations in Syria and Afghanistan; the group had made a shift from fundraising through charitable fronts to taking donations via blockchain technology (FATF, 2021).

Compared to traditional financial mechanisms, cryptocurrency transactions and assets are difficult to track and seize because they exist virtually within decentralized architectures. In recent years, decentralized currencies such as Bitcoins and USDT have gained popularity among terrorist groups because they operate independently of geographical boundaries, governmental oversight, central bank control, and identification requirements (Ogele, 2024). Terrorist organizations handle cryptocurrencies mainly in three ways- receiving, managing, and spending.

Terrorist groups have been using cryptocurrencies to raise and transfer funds for their activities. Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Monero are the cryptocurrencies that offer anonymity and decentralization to terrorist organizations while seeking funds for their activities. Terrorist organizations such as Al-Qaeda, Al-Nusra Front (ANF), and Hay-at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) have been using Bitcoins for their fundraising campaigns (Burgess et al., 2024). Hamas has also transitioned to non-custodial wallets from conventional digital wallets to hide their identities and has been using cryptocurrency fundraising efforts since 2019 (L. Rosen et al., 2024). Platforms such as Telegram and Twitter are used by terrorists to make their groups, spread their propaganda, and raise funds through Bitcoin donations.

Another use of cryptocurrencies is for managing operations. Terrorist organizations use funds generated through cryptocurrencies for regular activities, including general security, communications, and management. Weapon dealers, drug traffickers, human traffickers, and distributors of child pornography use cryptocurrencies to make their transactions secure and hidden (Dion-Schwarz et al., 2019). Also, hackers involved in illicit activities and ransomware attacks demand payment in cryptocurrencies. For example, ransomware attackers in Israel who were identified as terrorists demanded payment in Bitcoin.

New financial instruments such as smart contracts are the creation of cryptocurrencies and have revolutionized financial transactions. Smart contracts use blockchain technology to encode agreement terms, permit automated execution, and eliminate the need for intermediaries (Ogele, 2024). Blockchain technology of cryptocurrencies enables the quick and anonymous movement of funds across borders and helps terrorist organizations finance their activities without any intervention.

Crypto coins like Monero amplify the challenges for anti-terrorism groups as they make the user’s identities and transaction details difficult to trace (Dion-Schwarz, Manheim, & Johnston, 2019). Further, the adoption of bitcoins by these groups has exposed the regulatory gaps that exist globally. Around 35% of the countries across the globe lack robust oversight over cryptocurrencies. In addition to this, services like blockchain mixing make it extremely difficult to track down the sources of illicit funds (Weimann, 2018).

Evolving Strategies For Tackling Crypto Financing

Anonymity, lack of central regulations, global accessibility, and acceptability have promoted cryptocurrency as a reliable tool for fundraising, money laundering, and other illicit activities. To counter this, various governments across the globe along with national and international cooperation bodies have launched a range of measures to solidify their position in this fight against terrorism.

Blockchain Analytics

Blockchain transactions unlike traditional payments are recorded on a public ledger, making them traceable using the right set of tools. Companies like Chainalysis, CipherTrace, and Elliptic use blockchain analysis to uncover various transaction data and help authorities in identifying the patterns of illicit funding which ultimately helps them establish links between activities or operations and terrorist groups associated with them. In 2020, 2 million dollars were seized as authorities uncovered a network of Bitcoin transactions with the help of Chainalysis, the funds were flowing from public donors to certain wallet addresses, details of which were communicated using dark web forums (Dion-Schwarz, Manheim, & Johnston, 2019).

Tracking and Banning Privacy Coins

Crypto coins like Monero, Dash, and Zcash add an extra layer of anonymity posing a significant challenge to authorities (FinCen, 2023). Mentioning their obscure transaction amounts, wallet identities, and their role in money laundering and illicit financing, Japan in 2018 banned Monero and Zcash. Meanwhile, companies like CipherTrace have launched initiatives to partially de-anonymise transaction details of these coins (Reuters, 2018).

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning Detection

Using machine learning vast data sets can be analyzed for anomalies and can be used to identify outliers or obscure details from a huge data set of crypto transactions. The AI models can alert the authorities about high-risk activities and suspicious transactions like large transactions between two wallets or frequent use of mixing services. Major cryptocurrency exchanges like Binance and Coinbase use these tools to identify cases of crypto misuse and help authorities with actionable intelligence ( FATF, 2021).

Strengthening Regulatory Measures

Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Travel Rule

The FATF introduced the Travel Rule to fight the misuse of cryptocurrencies for illicit activities. The rule ensures transparency and accountability of crypto transactions. It makes it compulsory for Virtual Assets Service Providers (VASP) to collect and share information on transactions above US $1000.

In 2021 in a review by FATF, it was found that many countries had reported a 40% reduction in untraceable transactions after the travel rule came into effect. For example, South Korea mandated VASPs to enforce Travel Rule standards, significantly reducing illegal crypto activity linked to terror groups (FATF, 2021).

National and International Measures

Each country must establish methods and implement laws to counter their challenges along with actively participating in global cooperation to fight cross-border transfer of funds using crypto.

The Department of Justice of the USA used link analysis effectively to bust a 15-million-dollar Al-Qaeda network that was completely funded through Bitcoin. Meanwhile, the blockchain forensics technique was used by the Enforcement Directorate, in India to seize 3.5 million in the form of cryptocurrency which was linked to terror groups. Laws like the Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023, further help the government to have a check over crypto exchanges.

Global collaborations like the Budapest Convention provide a stage for nations to come together and facilitate the investigation of cybercrimes including the misuse of cryptocurrency. Article 25 of the convention makes it compulsory for member nations to effectively communicate and share necessary data and resources for misuse of crypto transactions. Meanwhile, Article 18 ensures the secure storage of data and helps authorities access essential information about transactions before they are anonymized. The convention currently has 68 signatories (WEF, 2024).

In 2020, the United Nations (UN) and FATF came together to help the West African countries strengthen their cryptocurrency regulations. Training programs were conducted for law enforcement agencies to track Bitcoin transfers linked to Boko Haram’s arms purchase deal. This helped Nigerian authorities to ban accounts holding over 1.5 million dollars in illicit funds (UNCT, 2023). During the 2023 G20 summit, the UN also stated the significance of global alignment of policies and mandatory and uniform KYC standards for all crypto exchanges. The UN also sought blockchain forensics training to be part of the global counter-terrorism efforts (Sonmez & Codal, 2022).

Conclusion

The evolving nature of terror financing, driven by advances in technology and the rise of cryptocurrencies is a reflection of the ever-changing nature of threats that terrorist activities inflict. While traditional fundraising methods such as charities, donations, state sponsorships, etc continue to be exploited, the rise of cryptocurrencies promising anonymity and decentralized transactions has introduced a new dimension to this challenge. Even though authorities have been responding with regulatory measures, blockchain analytics, and advanced detection tools like AI. Combating terrorist financing requires international cooperation, strict regulations, and continuous innovation to stay ahead in this ever-changing domain of financial crime. As terrorist networks adapt and innovate, proactive and adaptive strategies will be necessary to ensure global security while supporting the broader promise of emerging technologies.

References

Burgess, A., Hamilton, R., & Leuprecht, C. (2024). Terror on the Blockchain: the emergent Crypto-Crime-Terror nexus. Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-59547-9_9

Norton, D., & Chadderton, J. (2016). Understanding the funding mechanisms of terrorist organizations. Journal of Counter-Terrorism and Political Violence. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep04244.6.pdf

Jacobson, M. (2010). Charities and NGOs: Terrorist financing and the misuse of humanitarian aid. University Press. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10576101003587184

Normark, L., & Ranstorp, M. (2015). Terrorist financing and the role of money service businesses. Journal of Financial Crime. https://www.fi.se/contentassets/1944bde9037c4fba89d1f48f9bba6dd7/understanding_terrorist_finance_160315.pdf

Freeman, M., & Ruehsen, M. (2013). Financing terrorism: The movement of funds and the methods used by terrorists. Global Security Review. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26296981?seq=1

FATF. (2021). Enhancing the Understanding of Terrorist Financing Risks in West and Central Africa. Financial Action Task Force. https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/methodsandtrends/documents/terrorist-financing-west-central-africa.html

Chainalysis. (2020). The 2020 Crypto Crime Report. Chainalysis Insights. https://go.chainalysis.com/2020-Crypto-Crime-Report.html

Brill, A., & Keene, L. (2013). Cryptocurrencies: the next generation of terrorist financing? SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2814914

Dion-Schwarz, C., Manheim, D., & Johnston, P. B. (2019). Terrorist Use of Cryptocurrencies: Technical and Organizational Barriers and Future Threats. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3026.html

Ogele, E. P. (2024). Terrorist Financing in the Digital Age: An analysis of cryptocurrencies and online crowdfunding. Journal of Terrorism Studies. https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1121&context=jts

Rosen, L., Tierno, P., & S. Miller, R. (2024). Terrorist financing: Hamas and cryptocurrency fundraising. CRS Reports. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12537/2

Weimann, G. (2018). Going Darker? : The Challenge of Darknet Terrorism. Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/going_darker_challenge_of_dark_net_terrorism.pdf

FATF. (2021). Travel Rule Guidance: Ensuring Transparency in Crypto Transactions. Financial Action Task Force. https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/Travel-Rule-Guidance.pdf

Sonmez, F., & Codal, A. (2022). Global cryptocurrency regulations and their implications. Journal of Financial Crime Research.https://crimesciencejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40163-021-00163-8

Japan Financial Services Agency (JFSA). (2018). Japan Bans Anonymous Cryptocurrencies like Monero and Zcash. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/japan-cryptocurrency-ban-idUSKBN1OB0U3

UN Office of Counter-Terrorism (UNCT). (2023). Strengthening cryptocurrency regulations to combat terrorism: Lessons from West Africa. United Nations. https://www.un.org/counterterrorism/cct

U.S. Department of Justice. (2021). Bitcoin network linked to Al-Qaeda dismantled. DOJ Press Releases. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/global-disruption-three-terror-finance-cyber-enabled-campaigns

Budapest Convention on Cybercrime. (2001). Key Provisions to Combat Cryptocurrency Misuse. Council of Europe. https://www.coe.int/en/web/cybercrime/the-budapest-convention

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). (2023). Privacy coins and their implications on global anti-money laundering efforts. https://www.fincen.gov/news/news-releases/fincen-year-review-fiscal-year-2023

World Economic Forum (WEF). (2024). How global crypto regulations are changing: A review. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/05/global-cryptocurrency-regulations-changing/