Author: Kanika Kushwaha, Niharika Punia, Shreya Ranjan, Vikram A L

ABSTRACT

Childhood trauma significantly influences long-term psychological health, often contributing to anxiety, depression, PTSD, and maladaptive coping strategies. Neurobiological alterations, including amygdala hyperactivity, hippocampal shrinkage, and reduced prefrontal cortex activity, impair emotional regulation and memory. These changes highlight the necessity for early intervention and trauma-informed care. Effective treatments such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Trauma-Focused CBT (TF-CBT), and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) support recovery by promoting adaptive coping mechanisms. Continued research on trauma’s neurobiological effects is essential for refining therapeutic approaches and improving mental health outcomes, emphasizing the importance of addressing trauma early for lasting psychological well-being.

INTRODUCTION

Childhood trauma, encompassing emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, can significantly disrupt psychological well-being and neurodevelopment. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have been consistently linked to an elevated risk of enduring mental health challenges, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Felitti et al., 1998; Heim et al., 2008). Neurobiological alterations associated with trauma, particularly within the amygdala and hippocampus, have been shown to impair emotional regulation and memory processing, contributing to long-term psychological distress

A comprehensive understanding of childhood trauma’s long-term consequences is essential for advancing both scientific inquiry and clinical practice. Trauma survivors frequently encounter persistent emotional distress, diminished social functioning, and maladaptive coping patterns, underscoring the need for targeted, evidence-based interventions (Merrick et al., 2018). Investigating trauma’s neurobiological effects alongside effective therapeutic approaches can inform trauma-informed care, ultimately reducing long-term psychological harm and improving mental health outcomes.

Keywords: Childhood trauma, Psychological impact, Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), PTSD, Depression, Anxiety, Maladaptive coping, Emotional regulation, Targeted interventions, Trauma- informed care

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND CHILDHOOD TRAUMA

The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Emotional, physical, or sexual trauma experienced as a child can have a significant and long-lasting psychological impact on a person’s growth and general well-being. Childhood trauma has a complicated and multifaceted long-term psychological impact that frequently shows up in adulthood in ways that might make it difficult for a person to control their emotions, build healthy relationships, and deal with life’s obstacles. According to research, childhood trauma can change how the brain develops, especially in areas linked to stress response, emotional regulation, and interpersonal functioning. These changes may last far into adulthood (Anda et al., 2006).

The long-term psychological impacts of childhood trauma might include issues with mental health as well as identity and self-worth. People who have unresolved trauma may have feelings of guilt, shame, and inadequacy. Their self-esteem may be damaged and persistent emotional suffering may result fro

m these internalized unfavorable self-perceptions. Additionally, the trauma may result in maladaptive thought processes that reinforce emotions of hopelessness and powerlessness, such as catastrophizing, ruminating, or black-and-white thinking (Beck, 2011).

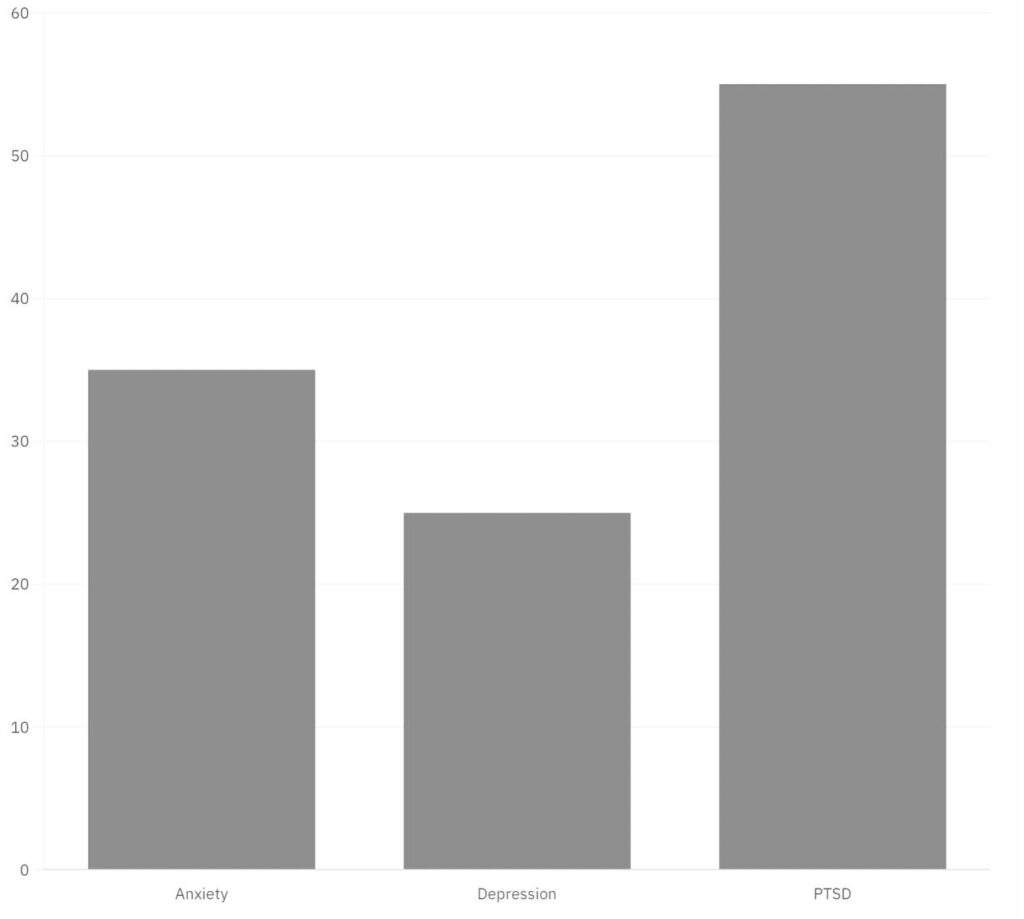

Description of the graph 1.1:

- Anxiety: Approximately 30-40% of adults who experienced significant childhood trauma develop anxiety disorders later in life. The CDC’s ACE study indicates that adults with higher ACE scores are 2 to 4 times more likely to report anxiety disorders.

- Depression: Childhood trauma increases the risk of adult depression by approximately 2.5 times. Studies report that 20-30% of individuals with a trauma history experience clinical depression during their lifetime.

- PTSD: About 50-60% of children exposed to severe trauma may develop PTSD symptoms. Adults with childhood trauma histories are three times more likely to be diagnosed with PTSD.

NEUROBIOLOGICAL ALTERATIONS IN TRAUMA SURVIVORS

Childhood trauma can lead to significant and lasting neurobiological changes, profoundly affecting brain structure, function, and stress regulation. Early traumatic experiences, such as abuse and neglect, disrupt normal brain development, particularly impacting the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (Heim et al., 2008). The amygdala, responsible for processing fear and regulating emotions, often becomes hyperactive in trauma survivors, resulting in heightened emotional reactivity and anxiety (Merrick et al., 2018). Conversely, the hippocampus, essential for memory formation, tends to shrink following trauma, leading to memory deficits and dissociative symptoms.

The prefrontal cortex, governing impulse control and decision-making, typically shows reduced activity, impairing emotional regulation and increasing impulsivity. These structural changes correspond with altered neurochemical activity, such as cortisol dysregulation and disruptions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a stress-response system affected by chronic stress during critical developmental periods.

Functional neuroimaging studies reveal disrupted connectivity among these brain regions, emphasizing trauma’s long-term impact on emotional and cognitive functions. Such changes are frequently associated with mental health disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety (Heim et al., 2008).

Key mechanisms driving these alterations include neuroinflammation and epigenetic modifications. Trauma can trigger neuroinflammatory responses, impairing synaptic plasticity and neural communication. Additionally, early trauma may alter gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms, influencing stress regulation and emotional responses well into adulthood (Merrick et al., 2018).

These findings underscore the profound and lasting effects of childhood trauma, highlighting the importance of early interventions and trauma-informed care to mitigate long-term psychological harm.

COPING FACTORS OF CHILDHOOD TRAUMA

Childhood trauma can have a lasting impact on a person’s physical, social and emotional well-being. These traumatic experiences can move into an individual’s adult life as well, usually constantly being reminded in the form of PTSD or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (if diagnosed) or simply, stress caused by past trauma. Hence, to manage the pain and distress caused by these events, individuals tend to develop certain coping mechanisms (Negele et al., 2015).

Two of these mechanisms include ‘Adaptive’ and ‘Maladaptive’ methods of coping. Adaptive coping, as the name suggests, involves healthy ways of management of trauma. This includes engaging in therapy such as CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) to process and learn healthier thought patterns. Mindfulness activities like meditation help remain grounded and reduce emotional reactivity. Social support given by close friends, family or groups with common interests provides validation and comfort. Physical activity such as running, exercising, yoga or hitting the gym causes endorphin production helping reduce stress and improving mood. Healthy coping mechanisms allow individuals to process their trauma, heal, and build resilience, leading to better overall mental health.

Maladaptive coping often includes avoidance where a person tends to disconnect themselves from their emotions and use substances to numb their pain and distress. Denial is when trauma is minimized, and repression is when painful memories are buried inside and ignored. Additionally, many survivors develop hypervigilance, which is when an individual is constantly alert due to perceived threats. Self-blame, also known as internalising guilt, is believing that the individual is responsible for the trauma. These mechanisms provide temporary relief but may be harmful in the long run. Numerous research studies have highlighted the detrimental impact of maladaptive coping on mental health outcomes. Individuals relying on avoidance, substance abuse, or denial as coping strategies often exhibit higher levels of anxiety, depression, and other psychological disorders (Sesar et al., 2010).

Over time, individuals may learn to shift from maladaptive to adaptive coping strategies, with therapy and support playing key roles in their healing journey.

THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES

The choice of intervention method largely depends on the type and severity of the issue and the age of the individual receiving the intervention. Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) is an approach designed for young children, especially those aged 0-6, who have faced trauma or mental health challenges. This method combines attachment theory with cognitive-behavioural techniques to help improve emotional regulation and strengthen the relationship between the child and their caregiver. In CPP sessions, the child and their primary caregiver participate, allowing them to work together to process their experiences and create a shared understanding of the traumatic event. This therapy aims to enhance the caregiver-child bond, leading to better emotional health and developmental outcomes for the child (Gregorowski et. al. 2013).

Other effective therapies for children dealing with trauma include Trauma Systems Therapy (TST) and Skills Training in Affect and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR). TST focuses on helping children develop self-regulation skills while reducing stress in their environment which could worsen trauma symptoms. STAIR specifically targets how children manage their emotions and relationships before addressing trauma processing. Additionally, Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT) addresses symptoms of PTSD through exposure therapy which helps children learn coping strategies while addressing trauma narratives (Casement & Swanson, 2012). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is another method that helps individuals process traumatic memories by simultaneously stimulating both brain halves using eye movements. For children, alternative methods like hand tapping on shoulders or feet have been successfully used instead of just eye movements, making it effective for single-event traumas (Spates et. al. 2007).

Pharmacological interventions, such as medications like SSRIs, can also be important in managing severe symptoms that interfere with normal development. Cognitive Restructuring helps children identify and challenge negative beliefs related to their trauma, promoting healthier thinking patterns. Psychoeducation provides both children and caregivers with an understanding of trauma reactions and treatment processes. Lastly, symptom monitoring and gradual exposure therapy help track PTSD symptoms and reduce anxiety by slowly introducing children to trauma-related cues (Murray et. al. 2015). Together, these various approaches create a comprehensive support system for helping children heal from trauma and thrive.

CONCLUSION

Childhood trauma profoundly affects psychological well-being, brain development, and emotional regulation, often leading to anxiety, depression, PTSD, and maladaptive coping strategies. Neurobiological alterations, including dysfunction in the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, further highlight the need for early intervention and trauma-informed care. Evidence-based therapies such as CBT, TF-CBT, and EMDR can promote recovery by fostering adaptive coping mechanisms. Continued research on trauma’s neurobiological impact is essential to refine treatment approaches and improve survivor outcomes. Addressing childhood trauma early can significantly reduce long-term psychological harm and enhance mental health across the lifespan.

REFERENCES

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

Beck, A. T. (2011). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Casement, M. D., & Swanson, L. M. (2012). A meta-analysis of imagery rehearsal for post-trauma nightmares: effects on nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and posttraumatic stress. Clinical psychology review, 32(6), 566–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.002

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American journal of preventive medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

Gregorowski, C., & Seedat, S. (2013). Addressing childhood trauma in a developmental context. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 25(2), 105-118. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2013.795154

Heim, C., Newport, D. J., Mletzko, T., Miller, A. H., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2008). The link between childhood trauma and depression: insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(6), 693–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008

Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. (2018). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011-2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(11), 1038. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537

Murray, L. K., Skavenski, S., Kane, J. C., Mayeya, J., Dorsey, S., Cohen, J. A., Michalopoulos, L. T. M., Imasiku, M., & Bolton, P. A. (2015). Effectiveness of trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy among trauma-affected children in Lusaka, Zambia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(8), 761–769. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0580

Negele, A., Kaufhold, J., Kallenbach, L., & Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. (2015). Childhood trauma and its relation to chronic depression in adulthood. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(5), 295-303. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/650804

Sesar, K., Šimić, N., & Barišić, M. (2010). Multi-type childhood abuse, strategies of coping, and psychological adaptations in young adults. Clinical Sciences, 51(5), 406-413. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2010.51.406

Spates, C. R., Samaraweera, N., Plaisier, B., Souza, T., & Otsui, K. (2007). Psychological impact of trauma on developing children and youth. Primary care, 34(2), 387–ix. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2007.04.007