Balancing Growth and Greed: Ethics, Justice, and Development in Emerging Societies

Authors: Vithika Goel, Varsha. G, Anisha Neogi, Joshua Oluwagbolahan, Ambuj Singh, Olalekan Falegan

Abstract

Economic growth in the emerging economies of modern societies, although essential, often comes at the cost of environmental degradation, rising inequality, and social disintegration (World Bank, 2023; IPCC, 2023). This research highlights that uncontrolled industrialization can lead to ethical compromises and crime concerns (UNDP, 2022; IMF, 2023). Using reliable data from global institutions, the study argues that public policy must move beyond facilitating growth to ensuring sustainability and equity (World Bank; UNDP; IMF). Without strategic monitoring, development becomes harmful rather than beneficial. Therefore, inclusive, ecologically balanced development is important (IPCC; Academic Journals, 2023) to align economic ambitions with environmental and social justice.

To address these issues, policymakers must prioritize green infrastructure, enforce environmental regulations, and expand social safety nets (UNDP, 2022; World Bank, 2023). Integrating climate adaptation strategies and equity-focused planning into the development agenda can reduce long-term risks (IPCC, 2023). Furthermore, transparent governance and international cooperation are essential to balance national development goals with global sustainability commitments (IMF, 2023; Academic Journals, 2023). A shift towards an inclusive policy model centered on ecology and human well-being is not just a recommendation, it is a necessity for the future sustainability of emerging economies.

Keywords: Growth, GDP, Sustainable, Climate Change, Policy, Equitable, Development

Introduction

As the pace of the 21st century hastens, economic growth has been a hope of promise and a field of contradiction. It has unmatched potential for poverty alleviation, infrastructure development, and the rise in the standard of living, especially for the world’s emerging economies. However, it also raises raw issues in the shape of widening inequalities, speeding up the pace of environmental degradation, and moral issues regarding the distribution of resources and administration.

For example, the World Bank predicts that sub-Saharan Africa’s urban population will double by 2040 and Southeast Asia’s digital economy will exceed $300 billion in 2025. But accompanying these growth narratives are also attached dark realities: more than 1.3 billion people worldwide remain in multidimensional poverty, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) estimates, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) tallies developing countries to carry an asymmetrical climate risk burden with the path of their industrial development.

Socio-economic inequalities, meanwhile, form the ground on which white-collar crime, ecologic crime, and organized violence ran amuck, gnawing away at social solidarity. Such trends are further buttressed by policy failures in which governing organizations are overwhelmed by the accelerating economic changes and respond with growth on the expense of sustainability and fairness. Through a multi-disciplinary study of such causative elements, this paper endeavours to inquire how the dynamics of economic growth within transition communities intersects with issues in environmental ethics, criminological trends, and public policy challenges. Drawing on facts and statistics of World Bank, IMF, UNDP, IPCC, and literature, the research seeks to illuminate both the danger of boundless growth as well as on the possible trajectory of equitable, sustainable, and inclusive growth and tries to provide useful information to policymakers, researchers, and practitioners to facilitate development for meeting the accumulating battle of growth vs greed in the age.

- Economic Growth and the Modern Society

Economic development remains a top measure of country development and societal advancement, oftentimes tracked using proxies like Gross Domestic Product (GDP), employment, infrastructure, and technology development. Countries such as India, Indonesia, and Vietnam have been recording good growth trajectories lately. During the fiscal year 2023-24, India achieved an 8.2% GDP growth rate, the highest among major world economies, according to the World Bank (2023a). Indonesia experienced a 5.0% growth rate in 2023, primarily driven by consumer demand and favourable commodity prices (World Bank, 2023b). Vietnam recorded a 5.0% growth rate with forecasts projecting an increase to 6.1% in 2024 on the back of robust manufacturing and export-driven economies (World Bank, 2023c).

As these economic gains are made, the fruits of labour are not distributed equally. Urban centres flourish with improved infrastructure, technology, and services, but rural regions lag, lacking basic services. This imbalance has led to broader societal transformations and greater recognition of the limitations of growth-oriented development patterns.

Urbanization and Infrastructure Strain

South Asia has experienced accelerated economic growth, and with this has come massive urbanization. Between 2001 and 2011, South Asia’s urban population increased by 130 million; another increase of nearly 250 million is anticipated by 2030 (Roberts, 2015). This has caused immense pressure on public infrastructure, including housing, transport, sanitation, and water supply systems.

Urban centres across the region are failing to provide affordable housing, and as a consequence, informal settlements are mushrooming. The public transport system is typically crowded and under-resourced, and the waste management system becomes overstretched, raising high public health and environmental challenges. Additionally, pressure on water and energy networks is increasing due to heightened demand and stress caused by climate change (World Bank, 2015).

Urban governance has failed to keep pace with these challenges. Administrative capacity and resources to apply long-term urban planning are non-existent in most cities. Such conditions bring about fragmented growth, unproductive use of land, and inefficient delivery of services. Improved urban strategies, increased investment, and institutional reforms that give powers to local government must be applied in order to address these issues.

The Ethics of Progress and Technological Advancement

Emerging societies increasingly look to technological innovation as a means of addressing structural inefficiencies and developmental gaps in their pursuit of economic growth and modernization. AI-powered governance systems and digital finance are just two examples of how technology is frequently hailed as the great equalizer. But beneath this assurance is a basic moral conundrum: at what cost and to whom does technological advancement benefit?

Innovation has the potential to increase access to healthcare, education, and financial inclusion while also streamlining service delivery. However, it also runs the risk of exacerbating already-existing disparities. For example, in many developing nations, socioeconomic disparities have increased due to the digital divide, which is the difference between those who have access to modern information and communication technology and those who do not (World Bank, 2021). Furthermore, an environmental ethics lens is frequently absent from technological innovation. There are serious ecological risks associated with the global push for digital infrastructure, from data centers to electronic waste. Communities in the Global South that are already at risk are disproportionately affected by environmental degradation caused by the extraction of rare earth minerals, excessive energy use, and inadequate recycling systems (Perkins, 2020).

Therefore, proactive governance is needed to align technology with the more general objectives of environmental sustainability and social justice. Transparent data governance frameworks, local innovation ecosystems, inexpensive internet access, and inclusive digital literacy must all be given top priority by policymakers. Furthermore, ethical accountability must be the foundation of public-private partnerships to guarantee that technological advancement advances society rather than strengthening current privileges.

Societal Transformation and Value Shifts

With the development of economies come shifts in values in society. Efficiency, productivity, and consumerism increasingly become the way of the day in public discourse and policymaking, and in many instances, issues of sustainability and social solidarity are relegated to the background. Sassen (2014) posits that economic globalization and urbanization are delivering new trends of inequality and social dislocation, especially among marginalized groups. These trends can contribute to alienation on a large scale, precarity in the workplace, and dislocation from conventional livelihoods.

The growth model of economics is inherently unsustainable (Jackson, 2009). He argues the case that economic growth in GDP terms is not inherently connected with improved well-being or environmental well-being. Instead, Jackson posits the rebuilding of prosperity based on ecological health, social fairness, and the quality of life. Jackson bemoans consumerism and requires institutional change in the manner of measuring progress by society and its distribution of assets.

Moreover, the United Nations study of 2019 indicates the unsustainable trajectory of current development approaches with growing carbon emissions, depletion of resources, and higher social disparities. This indicates that growth-based models, unless a paradigm shift takes place, will aggravate rather than rectify world issues.

- Econometric Analysis

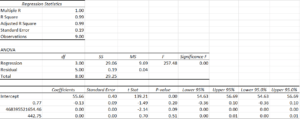

This analysis was done using data pertaining to India’s growth post the LPG policies in 1991. It contains data from 2000-2018. The variables taken are GDP, GDP per capita, FDI (as % of GDP) as the regressors and Population living in slums (% of urban population) as the regress and

Source: World Bank Data Bank

Findings & Limitations:

- GDP shows a negative relationship with the percentage of the population in urban slums, suggesting that higher GDP might reduce slum populations. However, this effect is not statistically significant (p = 0.1972).

- GDP per capita also has a negative impact, with higher GDP per capita potentially leading to fewer people in slums. Its effect is borderline significant (p ≈ 0.086), but more data is needed to confirm this trend.

- FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) shows a positive relationship with slum population percentage, but this effect is not statistically significant (p = 0.514), meaning no clear conclusion can be drawn from this variable.

- Overall model has an excellent fit (R² = 99.36%) but is limited by a small sample size (n=9), reducing the reliability of individual predictor results and the ability to generalize findings.

- Ecological Costs of Development

Economic development in emerging nations is often at the expense of the environment. Industrialization, deforestation, urbanization, and enhanced energy consumption all lead to environmental degradation. South Asian nations are among the most climate-vulnerable due to their patterns of development, as cited by the IPCC.

The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis predicts that environmental degradation first rises with economic growth but then falls as societies get richer and invest in cleaner technologies. This theory is, however, criticised for being too simplistic and failing to take into account irreversible ecological harm or global externalities.

Urban regions are especially plagued by issues like water and air pollution, waste management crises, and the destruction of green cover. Satellite imagery from NASA depicts growing rates of air pollution in Delhi and Jakarta and other cities, which are directly attributed to industrial and automobile emissions.

Findings

Deforestation and Land Use Change

Agriculture and urban sprawl are the primary causes of deforestation, lowering carbon sinks and threatening biodiversity. For example, Amazon rainforest destruction is directly related to agricultural expansion.

Biodiversity Loss

Development breaks up habitats and brings in pollutants, causing species to become extinct. The IPBES (2019) states that almost 1 million species are threatened with extinction due to human activity.

Water and Air Pollution

Industrial discharges, mining, and building release contaminants that worsen air and water quality. This has an impact on both ecosystems and human health.

Climate Change Contribution

Greenhouse gas emissions due to infrastructure development mainly come from fossil fuels and land use changes. These are contributing factors to global warming and weather extremes.

Ecosystem Services Degradation

Natural systems deliver services such as pollination, flood control, and soil fertility. These functions are usually disrupted during development, heightening exposure to natural disasters and lowering agricultural productivity.

Development without ecological consideration is unsustainable. The climbing environmental costs threaten both biodiversity and human well-being. A shift toward sustainable development that prioritises ecological health is fundamental for long-term prosperity and planetary stability.

- The Criminological Dimensions: Crime and Inequality in Growing Economies

Emerging modern civilisations are characterised by rapid socioeconomic developments, which create a complicated interaction with criminological landscapes. Although the quest for economic expansion provides avenues for advancement, it frequently results in socioeconomic inequalities that can act as a breeding ground for many types of criminal activity. Using reputable research and pertinent sources, this section examines the criminological aspects of the study, focusing on the connection between crime, inequality, and economic progress.

One major area of worry is the increase of white-collar crime in economies that are expanding quickly. The modernisation and integration of these societies into the global financial system provide more opportunities for sophisticated financial crimes like embezzlement, fraud, and corruption, especially in areas with weaker regulatory frameworks (Levi, 2007; Sutherland, 1949). When new economic sectors and capital inflows surpass the development of efficient governance systems, vulnerabilities are created that are taken advantage of by people and groups looking to benefit themselves illegally.

Environmental crime is a major problem in rising economies that are experiencing rapid industrialisation and resource extraction, as the literature also emphasises. In the pursuit of quick economic growth, short-term profits may take precedence over long-term ecological sustainability, creating an atmosphere that encourages pollution, illegal mining, and land acquisition. Such operations are extremely lucrative criminal enterprises, as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC, as quoted in the abstract) emphasizes (Wyatt, 2013; ñригaда, 2016). This problem is compounded by weak enforcement capabilities and possible coordination between corrupt officials and corporate entities, which leads to environmental deterioration and obstructs real sustainable development initiatives.

Finally, a criminological investigation must look at the relationship between social crimes and economic inequality. Excessive economic expansion often creates or increases already-existing disparities, resulting in the exclusion of large groups of people. Crimes including human trafficking, theft, and organised violence can flourish in informal settlements and urban slums, which are defined by limited access to opportunity, education, and proper law enforcement (браyн, Esbensen, & Geis, 2016). Therefore, the lack of inclusive growth techniques could hinder the advancement of society as a whole by contributing to a cycle of poverty and crime.

Development economics research frequently emphasises how rapid expansion can have unforeseen social and economic repercussions, such as making inequality worse (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). Environmental criminology focuses on the unlawful exploitation and degradation of natural resources, whereas criminological study continues to explore the ways in which those differences materialise as different types of criminal behaviour (South & Beirne, 2006).

The criminological lens shows a natural relationship between the growth of criminal patterns and the quest for economic prosperity in newly forming contemporary civilisations. A comprehensive knowledge of the connection between economic policies, social justice, environmental protection, and the establishment of strong law enforcement systems is necessary to effectively address these complicated issues. In order to foster more equitable and environmentally sustainable growth paths, this literature review lays the groundwork for a further investigation of these dynamics and the creation of strategic policy suggestions.

- Policy and Governance: Finding the Balance

In order to balance social justice, environmental sustainability, and economic growth, effective governance and policy are essential. Beyond conventional GDP measures, ecological and social indicators are incorporated into economic planning. The negative consequences of unbridled expansion can be lessened by putting laws into place that support sustainable agriculture, renewable energy, and fair resource allocation (Cobb & Daly, 1994). Additionally, encouraging participatory governance guarantees that a range of opinions are heard during the decision-making process, which raises the credibility and efficacy of development plans.

- Recommendations for Sustainable and Equitable Growth

In developing societies, the following multi-pronged proposals have been put forward to ensure that economic growth is consistent with social justice and environmental sustainability:

Green Economy Models:

Encouraging investments in green infrastructure, sustainable agriculture and renewable energy is essential to minimise damage to ecosystems while promoting development. The concept of circular economy reduces waste and slows environmental degradation by emphasising reuse and recycling of resources. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), a shift to a green economy has the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by half and create up to 60 million jobs worldwide (UNEP, 2013).

Inclusive Development Policies:

Social equity should be prioritised in development initiatives. It is essential to provide participatory urban planning, especially in informal settlements, and increase access to affordable housing, healthcare and education. The World Bank emphasises that inclusive policies reduce long-term inequality and enhance human capital.

Strong Institutional Frameworks:

Technologically advanced, accountable and transparent institutions promote good governance. E-governance portals and other digital governance tools enhance public participation and service delivery. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) believes that improving policy compliance and maintaining environmental standards depends on the effectiveness of regulatory bodies.

Cross-sectoral Collaboration:

NGOs, academia, the commercial sector and government should work together to develop and implement creative and flexible solutions. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), partnerships help mobilise resources and skills, especially for infrastructure that is socially inclusive and environmentally friendly.

Conclusion

When new modern societies begin down the road to economic growth, they stand at a fork in the road — one where decisions today will not only set national directions, but the course of the planet. The path to prosperity is paved with hard moral, environmental, and social dilemmas. Unrestrained growth has already taken us backward: greenhouse gas emissions rising, incomes growing more unequal, and a crime epidemic on urban peripheries. From the IMF, the world’s inequality has increased in leaps and bounds since the 1980s when the highest 10% now hold more than 50% of income worldwide, and in line with the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, if nothing is done, the world is heading full steam for climate catastrophes that will disproportionately hurt developing economies. And yet both of them present a singular window of opportunity for emerging societies to redefine what constitutes authentic progress. Instead of mimicking the exploitative trends of the previous industries, nations such as Costa Rica, where virtually 100% of the renewable resources have been exploited, and Bhutan where Gross National Happiness has been integrated into GDP ; provide exemplary examples of how growth can be balanced with sustainability and social bliss.

Inclusive development policies to plug gaps in health, education, and social protection can be undertaken, and green tech and circular economy programs can be invested in to reduce harm to the environment. The problem of the policymakers is seen: economic policy must transcend narrow GDP growth objectives and uphold environmental sustainability standards, social justice, and ethical decision-making. Institutional transformation to beat corruption, enhance environmental protection, and enhance openness will be needed. No less indispensable will be forging cross-sector collaboration that accesses the innovative strengths of the private sector, civil society, and the academe. New societies for this day and era have an option — they can set on a different track, one where growth and caring are united, innovation and ethics are synthesized, and aspiration and stewardship walk hand-in-hand.

The fate of world advancement hangs in the balance on whether nations can or will opt to embrace an ethical, equitable, and sustainable pattern of economic advancement. By this equitable means only is the vision of prosperity without greed gnawing into it may be achievable so that ongoing advancement need not deny future generations the right and legacy.

REFERENCES

- World Bank. (2023). World development report 2023: Migrants, refugees, and societies. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2023

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2023). Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

- United Nations Development Programme. (2022). Human development report 2022: Uncertain times, unsettled lives. https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2022pdf_1.pdf

- International Monetary Fund. (2023, October). World economic outlook: Navigating global divergences. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO

- Various authors. (n.d.). Articles in International Journal of Research in Law & Management. https://ijrlm.com

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2013). Green economy and trade: Trends, challenges and opportunities. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/green-economy-and-trade-trends-challenges-and-opportunities

- World Bank. (2022). Poverty and shared prosperity 2022: Correcting course. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/poverty-and-shared-prosperity

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). Regulatory policy outlook 2021. https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/oecd-regulatory-policy-outlook-2021-38b0fdb1-en.htm

- United Nations Development Programme. (2021). UNDP strategic plan 2022–2025: A future of possibilities. https://www.undp.org/publications/undp-strategic-plan-2022-2025

- Google, Temasek, & Bain & Company. (2021). e-Conomy SEA 2021: Roaring 20s — The SEA Digital Decade. Google. https://economysea.withgoogle.com/reports/

- Global Forest Watch. (2023). Deforestation rates and related data. World Resources Institute. https://www.globalforestwatch.org/

- Government of Bhutan. (2019). Gross National Happiness Index 2019. Gross National Happiness Commission. http://www.gnhc.gov.bt/en/

- International Monetary Fund. (2020). World inequality report 2020. https://wir2022.wid.world/

- International Renewable Energy Agency. (2020). Renewable energy statistics 2020. https://www.irena.org/Statistics

- IQAir. (2023). World air quality report 2023. https://www.iqair.com/world-most-polluted-cities

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2023). Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, H. Lee & J. Romero, Eds.). IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/

- NASA Earth Observatory. (2020). Air pollution levels over South Asian cities. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). Green growth indicators 2021. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/greengrowthindicators.htm

- United Nations Development Programme. (2023). Global multidimensional poverty index 2023. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indices/MPI

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2022). Global report on environmental crime 2022. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/environment-crime/index.html

- United Nations. (n.d.). Sustainable development goals. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- World Bank. (2020). Urban population growth (annual %). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.GROW

- World Economic Forum. (2023). The inclusive growth and development report 2023. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-inclusive-growth-and-development-report-2023/

- World Inequality Lab. (2022). World inequality report 2022. https://wid.world/news-article/world-inequality-report-2022/

- Jackson, T. (2009). Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. Earthscan.

- Roberts, M. (2015, September 20). Urbanization in South Asia: How is it going? World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/endpovertyinsouthasia/urbanization-south-asia-how-it-going

- Sassen, S. (2014). Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. Harvard University Press.

- Wyatt, T. (2013). Environmental crime: Key issues. Routledge.

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Publishers.

- браун, S. E., Esbensen, F.-A., & Geis, G. (2016). Criminology: Explaining crime and its context (9th ed.). Routledge.

- Levi, M. (2007). White-collar crime. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology (pp. 1749-1761). Springer.

- South, N., & Beirne, P. (2006). Green criminology. Ashgate Publishing.

- Sutherland, E. H. (1949). White collar crime. Dryden Press.

- United Nations. (2019). Global Sustainable Development Report 2019: The Future is Now – Science for Achieving Sustainable Development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/gsdr2019

- World Bank. (2015). Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia: Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Livability. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/sar/publication/urbanization-south-asia-cities

- World Bank. (2023a). India Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/india/overview

- World Bank. (2023b). Indonesia Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/indonesia/overview

- World Bank. (2023c). Vietnam Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/overview

- GSMA. (2022). The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2022. Retrieved from https://www.gsma.com

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2020). World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2020. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org

- Perkins, D. (2020). The Environmental Costs of Digital Technologies in the Global South. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(4), 537–554.

- UNCTAD. (2021). Data Protection and Privacy Legislation Worldwide. Retrieved from https://unctad.org

- World Bank. (2021). Digital Dividends: Leveraging Digital Technology for Development. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org

- Cobb, J. B., & Daly, H. E. (1994). For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy Toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future. Beacon Press.

- Hickel, J. (2020). Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown: An equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary. The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(9), e399-e404.

- Jackson, T. (2009). Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. Earthscan.

- Kovel, J. (2002). The Enemy of Nature: The End of Capitalism or the End of the World? Zed Books.

- Spash, C. L. (2002). Greenhouse Economics: Value and Ethics. Routledge.

- Reza, B. (2023). Understanding environmental costs in infrastructure development using emergy-based cash flow analysis. Journal of Environmental Management, 345, 120110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.120110

- Diaz, S., Settele, J., Brondizio, E. S., Ngo, H. T., & Guèze, M. (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. IPBES. https://ipbes.net/global-assessment

- Bateman, I. J., & Mace, G. M. (2020). The natural capital framework for sustainably valuing nature in development. Nature Sustainability, 3(9), 776–783. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0584-6

- (2023). Assessing the economic impacts of environmental policies. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/environment/assessing-the-economic-impacts-of-environmental-policies-bf2fb156-en.htm

- Li, J., Wang, S., & Liu, Y. (2021). Impact of urbanization on biodiversity: A global perspective. Science of the Total Environment, 771, 144800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.144800

- Sachs, J. D., Schmidt-Traub, G., & Mazzucato, M. (2022). Sustainable development planning for the 21st century. Global Policy, 13(S1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13118

- Sun, L., & Liu, Z. (2020). Modelling the ecosystem services degradation caused by infrastructure development. Ecological Indicators, 115, 106402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106402