Authors – Challa Rohan, Mahi Jaiswal, Shreya Chandrakanth Bhat, Thandokuhle Cleo Sibanda, Ismail Oladimeji Sanda, Annwesha Paith, Amanuel Mengistu

Keywords: Disability inclusion, Economic inclusion, Assistive technologies, PwDs (Persons with Disabilties), Rural Economy.

Introduction

“There is no greater disability in society than the inability to see a person as more,” — Robert M. Hansel.

With over 250 million people facing some form of moderate or severe disability; with classifications of what constitutes disability and its prevalence increasing over the past few decades, it becomes imperative for any nation to incorporate people with disabilities into the economic sector (Rashmi & Mohanty, 2024). This discussion predominantly occurs due to the very nature of disability. Disability is neither solely a medical nor a social phenomenon but, in fact, is a complex interplay between economic, social, medical, gender, and various other unforeseen vulnerabilities that human beings experience while being a member of a society. This can be noticed as causes for disabilities can be due to congenital disorders, accidents, ageing, or diseases, which in turn are exacerbated due to poverty, discrimination, or multiple forms of psychological trauma due to social exclusion.

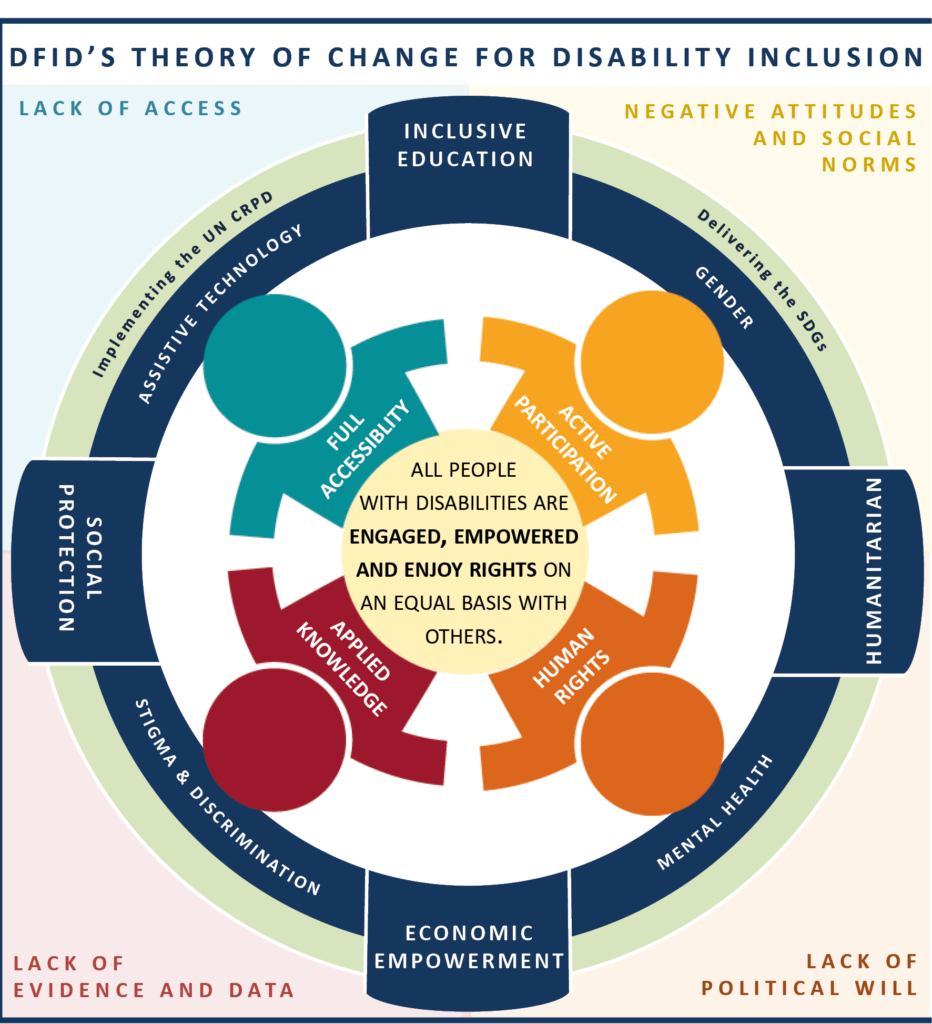

With the very nature of disability being complex, it falls under a few of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), of which India is a signatory to. India is projected to be the fastest growing economy while housing about 50-80 million people with disabilities according to the World Bank report. This causes there to be a necessity to understand how to incorporate the Persons with Disabilities (PwDs) to yield positive results to the economy. In this context, while using secondary sources, the paper reviews the status of PwDs within India with reference to Indian economy as a whole; it discusses the historical roots, the labour markets, the rural economy, and various contemporary studies pertaining to assistive technologies, accessibility of infrastructure, and analysis of class disparities. Building upon the previous discussions, this paper subsequently outlines long-term investment strategies that India ought to adapt to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030.

Historical Background and Grassroots Development for the Persons with Disabilities in India

People with disabilities have long experienced marginalization, isolation, and societal prejudice in India. Inequity in access to basic resources like education, healthcare facilities, jobs, and social engagement, as well as poverty and physical stress, are common experiences for people with disabilities (PwD). In India’s 2011 Census, around 26.8 million persons, or 2.21% of the total population, were classed as disabled (Minhas, 2023). However, researchers suggest that because of stigma and underreporting, this number might be lower than the true numbers.

The 2016 Act of Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD)

For a long time, people with disabilities were excluded from mainstream development because they were seen through a welfare lens. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Act of 2016, which highlighted the transition from charity to rights-based approaches, superseded the Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act of 1995 (Veena et al, 2023). Interestingly, with the addition of 15 disabilities, including those with dwarfism, acid attack victims, autistic spectrum disorder, and special learning disabilities, the RPWD Act has extended protection to a wider segment of the population than the 1995 Act; which only covered seven disabilities (Veena et al, 2023).

Empowerment Initiatives and Post Economic Reforms

In order to empower people with disabilities in a variety of fields, the Indian government has also launched a number of projects. In addition to requiring inclusive education, employment reservations, and accessible infrastructure, the Rights of Persons with impairments Act, 2016 was a landmark law that increased the number of recognized disabilities from seven (7) to twenty-one (21) (Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, 2024). However, initiatives like the Accessible India Campaign (AIC), which promotes barrier-free access to public spaces, are managed by the Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities within the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, 2023). Support for students with disabilities is provided by programs like Inclusive Education for Disabled at Secondary Stage (IEDSS) in the education sector. The objective of these endeavours is to guarantee economic autonomy and social engagement for those with disabilities in India.

Meanwhile, India’s post-1991 economic reforms increased growth but failed to include people with disabilities, which restricted their access to welfare programs and employment opportunities (Seema, 2023). Implementing inclusive policies is still essential for fair growth. Therefore, it is essential to include people with disabilities in order to guarantee social justice, equality, and sustainable development.

Analysis of policies or activities undertaken by the Indian Government to resolve class disparities due to disabilities

The Government of India has undertaken numerous policy interventions and initiatives to address and mitigate the class disparities faced or experienced by persons with disabilities (PwDs) in India. The initiatives are not only a welfare-based approach but can be majorly concluded as a rights-based approach for the PwDs, which outlines a framework to acknowledge participation and inclusion of PwDs as a human right rather than just a welfare activity of the society.

The foundation of India’s disability inclusion policy is the Right of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016. This Act of 2016 replaces the previous Act, i.e. Persons with Disabilities Act 1995. The law came into being with India’s ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Rao T S et al. 2016). This change increased the recognition of some disabilities from 7 to 21, considering a wide range of disabilities and inclusivity. In terms of the economic inclusion of PwDs, the government has increased reservation quotas from 3% to 4% for job reservations and 4% to 5% for education reservations. The Assistance of Disabled Persons for Purchase/Fitting of Aids/Appliances (ADIP) Schemes offers essential assistive devices to qualified PwDs (Madan et al. 2024). The scheme utilizes income as an eligibility criterion for covering the cost of aids and assistive applications, entirely for individuals with an income up to Rs. 22,500 per month, and covers up to 50% of the price for the same for individuals with income ranging between Rs. 22,500 and Rs. 30,000(NHFDC).

The Deendayal Divyangjan Rehabilitation Scheme (DDRS) funds Non-government Organizations for rehabilitation initiatives such as early interventions, model projects, special schools, and so on. The collaboration of community-led initiatives aids the government’s capacity to tackle disparity issues. The Accessible India Campaign (Sugamya Bharat Abhiyan) was initiated by the Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities and pivots on creating accessible spaces, transportation, and information ecosystems to eliminate the basic obstacles that keep PwDs from active citizen participation in economic activities.

While a great initiative tries to mitigate the disparity, there are certain significant implementation gaps. The allocation of resources for the programs for PwDs has witnessed only a 9% increase between 2016-17 and 2020-21, despite a doubling of policy components. Despite DDRS, the non-government organizations have difficulty hiring qualified professionals in rural areas. Since the recent amendment to the rule in 2017, the certification timeline has ranged from one to three months, aggravating delays. Rural areas usually lack qualified doctors and medical infrastructure for assessment purposes, which is a requirement for a Disability certificate (Math et al. 2019). Despite reservations or mandates and DDRS, 75% of children aged 5 and up to 25% of children aged 6 to 19 remain out of school due to inadequately trained teachers and curriculum. The omission of disability related questions from the NFHS-6 survey continues to perpetuate gaps in the data, giving it addresses only 5 types of disabilities despite the Act acknowledging 21 different types of disabilities. The current policy needs regular revision depending on the current situations and problems.

Growth of Persons with Disabilities in Indian Labour Market

India’s labour market holds immense untapped potential for people with disabilities (PwDs), with over 30 million employable individuals facing systemic barriers to inclusion. India’s push to integrate PwDs into the workforce reveals a paradoxical landscape of progress overshadowed by systemic gaps. Despite progressive laws like the Rights of PwD Act (2016), which mandates a 4% job quota, only 36% of PwDs participate in the labour force compared to 60% of non-disabled adults. Disabled women face stark exclusion, with employment rates at 23% according to the NSO 76th Round of Survey (National Statistical Office [NSO], 2019). Over 90% of PwDs remain trapped in informal roles in agriculture, small trades, or home-based crafts, which lack social security or fair wages, while nearly half of listed companies report zero disabled employees, exposing weak enforcement of quotas. Yet, there are initiatives by Tata Steel like “Ananta Quest,” which employs over 100 PwDs after retrofitting facilities with assistive technology (Tata Steel CSR Report, 2023), and Future Generali Insurance has increased its disabled workforce from 16 to 41 in 2023 (Future Generali India, 2023). However, wage gaps persist because, according to the Indian Economic Survey, PwDs earn 8-12% less hourly, in comparison to their non-disabled peers. Most importantly, accessibility remains a hurdle because only under 25% of workplaces meet basic standards, despite government schemes like the Accessible India Campaign (Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, 2023). Accessibility is the very first and crucial step towards inclusion and growth of PwDs in the workforce.

The corporate sector in India increasingly views inclusion as a strategic advantage, with job postings for PwD roles rising by 30-40% from 2020 to 2023, according to the LinkedIn Workforce Report. However, their representation in leadership is almost non-existent. Bridging this chasm requires urgent action like enforcing quotas with penalties, improving accessible infrastructure, and prioritizing skill development through government initiatives like PM-DAKSH’s geotagged job portals. The cost of inaction is heavy, as India loses an estimated ₹4.5 lakh crore annually due to PwD exclusion. Yet, the real loss is human potential, as a considerable number of PwDs remain sidelined in low-productivity roles despite having proven their capabilities, as we can evidently see in Mirakle Couriers’ hearing-impaired logistics team and SAP Labs’ visually impaired coders (SAP Diversity Report, 2023). The path forward requires not only policy reformations but also a cultural shift, treating inclusion as an economic imperative rather than charity. Disability rights rightfully advocate that meaningful change requires dismantling attitudinal barriers alongside infrastructural ones. The blueprint towards inclusion already exists, but what’s missing is the collective will to transform sporadic success stories into systemic equity.

Disability Inclusion in India’s Rural Economy

India being projected as the fastest growing economy by the IMF in their World Economic Outlook report while having about 70% of its workforce residing in rural India which also subsequently constitutes 46% of the national income; portrays the important role played by the rural sector in the Indian economy (World Economic Outlook, April 2025: A Critical Juncture Amid Policy Shifts, 2025). With such demographic status, it becomes imperative for India to consider how to manage and incorporate the Persons with Disabilities(PwDs) into the labour market in the rural sector. The reasons for considering PwDs can be due to positive relation to the economy as noted by the International Labour Organization which states inclusion of PwDs can result in a global GDP boost of 3-7% (Demirag, 2023). Alternatively, a negative relation which demonstrates that the PwDs living in rural areas not only experience greater challenges with access to basic amenities but also manifest a two-way negative relationship between disability and poverty, disability and income (Gaiha et al., 2022).

A detailed econometric analysis conducted by Gaiha et al. (2022) on the topic “Rural Poverty and Disability in LMIC’s” using the data from the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) of 2005 and 2012, has noted several observations. According to Gaiha et al. (2022) observations, contrary to common perceptions, two-thirds of the rural income is generated through non-agricultural activities due to rapid diversification of the rural economy. That being said, it is noted that this growth still did not bring out significant employment gains or reduce the disparity between the farm and non-farm productivity. The other observations include the prevalence of disability is 9.70% in the rural population, of which more than 50% suffer from 2 to 4 disabilities. Gaiha et al. (2022) observations on employment note that the population of unemployed among the disabled in rural India is just under 50% while the highest form of employment is part-time, which is >240 hours and <2000 hours. It is also noted that the people with disabilities and NCDs (Non-communicable disease) are less likely to be able to secure long duration part-time or full employment. The analysis also noted the people from general caste display lower probability of being extremely poor or being in the middle class but higher probability of being affluent in 2012 when compared to 2005 data. While stating that it is the complete opposite case for SCs and STs (Gaiha et al., 2022).

While all the relevant data is taken into consideration, there have been multiple initiatives taken by the government and international organizations to address these problems and support the development of industries to increase productivity and support mechanisms. Such as, the initiative by the International Labour Organization named “SPARK” which builds using systemic action learning-based approach, such as setting up representative bodies within a nation, coordinating, monitoring and collecting relevant data for inclusion (Sparking Disability Inclusive Rural Transformation (SPARK), 2024). The IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development) supported economic growth in rural India by co-financing initiatives such as Integrated Livelihoods Support Project and Andhra Pradesh Drought Mitigation for agricultural development of the rural economy (Gaiha et al., 2022).

The Role of Assistive Technology in Economic Growth: A Review of The Indian Economy Through the Inclusion of Persons With Disabilities

In the pursuit of an inclusive and future ready economy, the integration of assistive technology (AT) is not merely a supplementary consideration, it is central to equitable development. For over 26 million persons with disabilities (PwDs) in India, as per the 2011 Census, access to AT is not about convenience alone; it is fundamentally about access, participation, and dignity. These are the essential elements that enable individuals to engage fully in education, employment, and mobility within society domains where structural barriers often persist.

India’s been moving in the right direction, policy wise slowly, maybe unevenly, but still The 2006 National Policy for Persons with Disabilities set the tone in broad strokes, a vision for inclusion. Then the RPWD Act in 2016 came in with more teeth Legal backing and a longer list of recognized disabilities mandates around accessibility and AT. It was a shift from hoping things would improve to having some form of material impact on the society at large.

Under SDG 4 (Quality Education), AT has the potential to transform classrooms. Imagine a child whose blind being able to access a textbook the same day as their peers. It’s the kind of moment that can change a life. Though, there are schemes like Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan that are meant to support this kind of inclusive education; but then you hear stories of schools without trained staff, devices gathering dust, kids falling through the cracks. Because the intent is there.

Similarly, under SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), the employment of PwDs remains a critical challenge. Despite legal provisions and growing recognition of the economic benefits of inclusion endorsed by institutions such as the International Labour Organization (ILO) many PwDs remain confined to informal employment or unemployment. AT has the potential to improve workplace adaptability and productivity, yet private sector engagement remains limited. This may be attributed to perceived financial risks or a lack of awareness regarding the long term economic benefits of inclusion.

AT also plays a pivotal role in advancing SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities). However, systemic barriers persist. Accessibility initiatives such as the Accessible India Campaign and the Smart Cities Mission have led to improvements in urban areas, but rural regions remain underserved. Additionally, the fragmented approach to training, affordability, and service delivery limits the impact of these initiatives.

A significant structural challenge lies in the AT market itself. Most assistive devices available in India are imported, resulting in high costs that make them inaccessible to large segments of the population. This situation is further exacerbated by low digital literacy and inconsistent service infrastructure, which together hinder the widespread and effective use of AT. The gap between policy intention and practical implementation is akin to constructing a bridge that only extends halfway; it reflects the incomplete realization of otherwise promising solutions.

Review Of Development Of Accessibility & Infrastructure With Reference To The Vision For Viksit Bharat 2047

The development of inclusive infrastructure is a cornerstone for empowering persons with disabilities and ensuring their full integration into society and the workforce. In India, there’s a growing push for more inclusive growth, especially under the government’s vision of Viksit Bharat, which is all about giving everyone equal opportunities and participatory development. Integration of PwDs not only addresses social justice but also stimulates economic development, and over 63 million people in India are found to have disabilities.

Advancements in Inclusive Infrastructure

The Accessible India Campaign (Sugamya Bharat Abhiyan), which started in 2015, was launched to make public spaces easier for everyone to use. While commendable efforts have been made, significant obstacles still exist. Varshney and Chandra (2024) observe a scarcity of qualified experts in universal design, resulting from the gaps in architectural education. In urban environments, there is the need for accessible transportation systems and public awareness to overcome persistent social and infrastructural hindrances.

Assistive technologies (AT) play a progressive role in infrastructure accessibility. When AT’s are affordable and culturally accepted, they significantly improve users’ independence and access to education and employment (Rao et al. 2024). Communities that embrace inclusive practices see greater adoption and impact of such tools.

Inclusive education is essential for future workforce participation. Kapil, Sujathamalini, and Halder (2024) demonstrate that Universal Design for Learning (UDL) enhances learning outcomes for children with intellectual disabilities and better prepare for them for employment. Meanwhile, the lack of digital accessibility training in India’s computing education, limits the development of inclusive digital systems. Addressing this gap is key to equipping future professionals to build accessible technologies.

Economic Impact of Disability Inclusion

Disability inclusion has the potential to unlock significant economic growth. According to RoboBionics (2024), integrating PwDs into the workforce and economy can expand India’s GDP by billions of dollars annually. A more inclusive society boosts consumer demand, innovation, and workplace productivity. Accessible workplaces reduce employee turnover and foster loyalty, while inclusive hiring practices widen the talent pool and fuel business competitiveness. Disability-led innovation, such as adaptive devices and inclusive technologies, can generate new markets, particularly in healthcare, education, and assistive tech. Thus, investing in inclusive infrastructure is not only ethically sound but also economically strategic for a rapidly growing economy like India’s.

Achieving the vision of Viksit Bharat needs more than just good laws, it needs action and a real sense of purpose. By building inclusive infrastructure, making education accessible, supporting assistive technology, and fostering inclusive workplaces, India can revamp disability inclusion into a real boost for the country’s growth. With everyone working together and strong political commitment, we can make inclusivity the building block for a stronger and more successful India.

Long term Investment Strategies for Economic Growth

Inclusive economic growth calls for economies such as India to employ robust long-term investment strategies that create conducive learning opportunities as well as income-earning opportunities for persons living with disabilities. Empowering PwDs through targeted long-term investment in areas of education and entrepreneurship can potentially enhance individual capabilities but also contribute to the nation’s economic development.

Education

Ensuring quality education is one of the basic human rights; however, for many children suffering from disabilities in India, education discrimination still prevails. Financial resources must be allocated towards more inclusively focused education framework models so that children with disabilities can fully engage with the education system. An education system must focus on enabling every child to succeed, irrespective of their capability (Kumar et al., 2021). The setting up of special vocational training centres is an equally important adjustment. Educational institutions need to address and teach relevant skills needed in the marketplace to disabled people for them to have meaningful employment (Mehta & Gupta, 2022).

Building mutually beneficial partnerships between schools, local businesses, and community organizations can enhance educational outcomes. These collaborations can create programs such as internships and practical training opportunities that not only provide real-world experience but also help eliminate societal stigmas around disabilities. They also help bridge the gap between attaining an education and being able to put it to use, either through employment or entrepreneurship. Providing quality education that results in practical knowledge and skills sets the foundation for a more inclusive workforce, aligning with the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on quality education.

Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship offers an alternative pathway to creating sustainable livelihoods, especially in the context of physical constraints, unemployment, and discrimination. It enables people living with disabilities to break barriers and attain self-sufficiency. Encouraging enterprises led by persons with disabilities (PwD) can stimulate economic activity, improve the job market, and allow for reinvestment into systems and infrastructure that continue to enhance the living and working conditions for PwDs. Inclusion, according to Chaudhary and Bhatt (2021), comes from far-reaching investments in mentorship and funding initiatives. For example, provided with microfinance and business management training and digital skills, PwDs would be empowered to start their own businesses.

Additionally, providing support for active ventures or businesses that promote inclusiveness accelerates adaptation. Gosh and Prakash (2021) maintain that promoting a proactive culture to support entrepreneurship with no regard to physical and mental challenges strengthens inclusion.

To effectively implement these strategies, a human-centered policy framework is essential. One that is driven by data, guided by real human experiences. Thus, comprehensive community engagement initiatives that not only raise awareness and foster acceptance of PwDs, but also inform policymakers of the living and working conditions and how best they can be improved and tailored.

Conclusion

India’s commitment to disability inclusion has shifted from a welfare-based to a rights-based paradigm, particularly since the passage of the RPwD Act in 2016, which enlarged recognized disabilities and mandated inclusive infrastructure, education, and employment. However, implementation gaps continue, especially in rural regions, due to limited resources, low knowledge, and infrastructural limitations. Initiatives such as the Accessible India Campaign and assistive technology (AT) programs have accelerated development, but still face obstacles in size and accessibility. Inclusive education and skill development remain critical for enabling economic participation for people with disabilities (PwDs), as supported by programs such as Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan and ADIP. Yet, data gaps, untrained personnel, and low digital accessibility hinder long-term outcomes.

Economic inclusion of people with disabilities is crucial, and research indicates that there is substantial potential for GDP growth. Investments in AT, accessible infrastructure, inclusive entrepreneurship, and supporting legislative frameworks can help to drive this growth. Poverty, underemployment, and the intersectional disadvantages that historically marginalized communities suffer continue to pose significant challenges to rural participation. Nonetheless, public-private innovations and international alliances (such as the ILO’s SPARK) provide intriguing models. Therefore, transforming intent into impact necessitates strategic investments, accountability, and political will. By focusing on disability inclusion in national development, India may achieve Viksit Bharat’s vision of resilience, equity, and economic empowerment.

Sub-themes and their authors:

- Challa Rohan Naidu – Introduction | Disability Inclusion in India’s Rural Economy

- Mahi Jaiswal – Review Of Development Of Accessibility & Infrastructure With Reference To The Vision For Viksit Bharat 2047

- Shreya Chandrakanth Bhat – Analysis of policies or activities undertaken by the Indian Government to resolve class disparities due to disabilities

- Thandokuhle Cleo Sibanda – Long term Investment strategies for Economic Growth

- Ismail Oladimeji Sanda – Historical Background and Grassroots Development for the Persons with Disabilities in India | Conclusion

- Annwesha Paith – Growth of Persons with Disabilities in Indian Labour Market

- Amanuel Mengistu – The Role of Assistive Technology in Economic Growth: A Review of The Indian Economy Through the Inclusion of Persons With Disabilities

References

Demirag, M. M. (2023, December 3). India, disability inclusion and the power of ‘by.’ The Hindu.

Future Generali India Insurance Co. Ltd. (2024). Annual report 2023-24.

PARLIAMENT QUESTION: EMPOWERING DISABLED PERSONS. (n.d.). Retrieved May 29, 2025

Samagra Shiksha: Paving the Way for Inclusive Education in India. (2023, December 5).

SAP 2023 Diversity and Inclusion Report. (n.d.). SAP.

Sugamya Bharat abhiyan. (n.d.).

Tata steel. (n.d.). Tata Steel | Corporate Social Responsibility. Tata Steel.

World Economic Outlook, April 2025: A Critical Juncture amid Policy Shifts. (2025, April 22). IMF.