Keywords:

Rural Inflation, Poverty, Cost of living, Basic amenities, Healthcare access, Food Insecurity, Education affordability, Housing crises, India and Nigeria, Low-income households

The Impact of Inflation on Access to Basic Amenities in Rural Communities: A Comparative Study of Nigeria and India

Introduction

Inflation in rural areas has emerged as a critical global concern in contemporary times, significantly affecting the well-being and resilience of rural households. As the prices of basic necessities continue to surge, rural families are finding it increasingly difficult to meet their daily needs, especially in the essential areas of food, housing, education, and healthcare. These four pillars, which form the backbone of human development, are being eroded by persistent inflation, threatening the very fabric of rural life.

One of the most pressing issues is the intersection of food basket inflation and limited employment opportunities. The rising cost of staple foods, coupled with stagnating or informal income sources, has created a severe resource deficit in rural households. This financial strain forces families to make harsh trade-offs, such as choosing between nutritious meals and medical care, or between school fees and house repairs, thereby compounding their vulnerability.

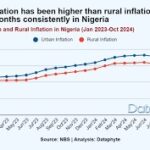

Compared to their urban counterparts, rural households are disproportionately affected. Factors such as lower per capita income, limited access to technology, poor infrastructure, and fewer formal employment opportunities widen the rural-urban divide. While urban residents may have relatively better access to social safety nets or diversified income streams, rural populations often lack the institutional and economic buffers needed to withstand prolonged inflationary shocks.

- Literature Review

Food inflation poses a critical challenge to rural households’ food security in both Nigeria and India. In Nigeria, rising food prices severely impact household access to sufficient, nutritious food, leading to decreased dietary diversity and increased vulnerability to economic shocks, especially among rural communities that rely heavily on agriculture and limited market access (Anugwa & Ugwu, 2022). Similarly, in India, food inflation reaching 10.9% in 2024 has intensified the financial burden on rural families, where over half of income is spent on food, resulting in limited accessibility and negative health outcomes like malnutrition and anemia. Factors such as global commodity prices, crop focus on staples, and supply chain inefficiencies aggravate the situation (Fathima, 2024). Both contexts underline the urgent need for long-term interventions, including improving agricultural productivity, crop diversification, strengthened supply chains, and effective social support systems like cash transfers and efficient Public Distribution Systems, to enhance food security and rural resilience to inflationary pressures.

Food basket inflation leads the people in African households to cope with scarcity of food with educational investment of their children (Obibuba,2024) . These not only have physical and medical implications but the psychological implications as well. The similar cases have been observed in the Indian subcontinent region as well where the scenario has worsened with a disproportionate rise of income and educational expenses (Bhattacharjee, 2016). Food basket inflation impacts the foundational block of the society, i.e., the educational sector of the society.

Inflation also significantly affects healthcare in low and middle income countries by driving up costs and reducing access. According to Uzor et al. (2024), inflation in Nigeria has driven significant increases in medicine prices, particularly in private pharmacies, due to currency devaluation and import dependence. This has led to reduced access and frequent stock-outs in public health facilities. Similar to this, Poongavanam et al. (2023) note that India’s healthcare system faces rising costs fueled by technology use and a growing chronic disease burden. To mitigate these effects, Uzor et al. (2024) recommend strengthening local drug production and expanding insurance in Nigeria, which also aligns with Poongavanam et al. (2023) call for cost control policies and investment in India’s primary healthcare infrastructure.

Inflation also severely affects fundamental sectors such as education, housing, and healthcare in low- and middle-income countries. Food basket inflation drives African households to divert resources from children’s education to survival needs, leading to long-term psychological and developmental setbacks (Obibuba, 2024). Similar patterns emerge in the Indian subcontinent, where income stagnation and rising educational expenses deepen inequalities (Bhattacharjee, 2016). Inflation also strains healthcare systems. In Nigeria, it raises medicine prices due to currency devaluation and import dependency, leading to frequent public sector stock-outs (Uzor et al., 2024). India faces parallel challenges from technology-driven costs and chronic disease burdens (Poongavanam et al., 2023). Mitigation strategies include boosting local drug production and expanding insurance (Nigeria) and investing in primary healthcare (India). Additionally, in rural India and Nigeria, inflation in construction materials has made housing unaffordable for the poor, undermining dignity and health security (Chattopadhyay et al., 2022; Adebayo & Iweka, 2020).

- Impact of Inflation On Accessibility To Food

Food is one of the basic necessities of life. The Constitution of India also includes the right to food in Article 21 i.e. right to life. But due to rising inflation in recent years, has resulted in soaring prices of food communities and this has impacted the accessibility of food mainly to the rural population. The data of the Ministry of Statistics and Implementation states that there has been an inflation of around 9.03% in December 2023, 9.10% in November 2024 and 8.56% in December 2024 (MoSPI 2024, CPI). This rise in inflation has led to a rise in the prices of food which has fueled the already dreaded issues like malnutrition, undernourishment and consistent health problems. India’s Global Hunger Index in 2024 stood at 27.3(Welt Hunger Hilfe, GHI 2024) which was classified as ‘serious’. Another reason for such inflation is rise in the crude oil prices, which shot up in 2021, after COVID-19. The main cause behind this was the recent rise of the market after a year of sluggishness during 2020. People have cut on their food intake to combat the effect of inflation. This has led to consumption of seriously nutrition-less foods. This has resulted in high levels of anemia in women and children at 57% and 63% respectively (MoHEW, NHFS-5 2019-21).

A similar situation could be witnessed in Nigeria but the condition is far worse. With inflation as high as 38% in August 2024 (Nigeria Food Inflation) food prices skyrocketed. Consequently, the people have been compelled to adopt coping strategies such as reducing meal portions, skipping meals, or resorting to less nutritious, cheaper foods. These adjustments have led to malnutrition, especially among vulnerable groups like children, pregnant women, and the elderly, thereby increasing the risk of stunted growth, weakened immune systems, and susceptibility to diseases. The malnutrition has also resulted in health issues such as diarrhoea and tuberculosis. The food prices escalated due to multiple intertwined factors—such as climate change, which caused droughts and reduced crop yields; high production costs driven by expensive inputs like fertilizers and seeds; and fluctuations in global oil prices that influence transportation and energy expenses. These trends were further exacerbated by the global changes in oil prices, which led to high transportation costs, one of the main causes of inflation.

To address this issue, the governments of both India and Nigeria must introduce new policies relating to controlling inflation. Along with this, access to food must be made available to the needy through the public distribution system, which would increase nutrition in their diet. In addition, proper minimum support prices must be provided to farmers to increase the production of food grains and the problems relating to irrigation must be addressed in order to increase the yield. This will lead to increased access to food and thus, improve the health of the people.

The struggle for food security in rural regions often forces households to cut costs elsewhere most commonly in housing. When food prices surge, families are left with little to invest in stable shelter. This trade-off traps them in unsafe or temporary housing, compounding vulnerability to economic shocks and natural disasters.

- Impact of Inflation on Cost of Living in Rural Communities: The Housing Crisis

Inflation has quietly but devastatingly reshaped rural life, and perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in the challenge of securing a stable home. Across villages in both India and Nigeria, building or maintaining a house has become increasingly elusive (Chattopadhyay et al., 2022; Adebayo & Iweka, 2020). For many families, a home is far more than bricks and mortar it is the foundation of dignity, safety, and a future. But in the current economic climate, this aspiration is slipping further out of reach.

In Bihar, India, Sita Devi was once hopeful. Two years ago, under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY-Gramin) scheme, she began planning a modest two-room pucca house with the help of a ₹1.2 lakh government subsidy. At the time, it seemed within reach. But since then, the prices of cement, iron, and sand have nearly doubled. What was once sufficient now barely covers half the construction cost. Like many others, Sita continues to live in a fragile mud hut, vulnerable to monsoon floods and searing heatwaves.

Amina Lawal, a farmer in Kaduna, Nigeria, tells a parallel story. She too began building her home with the help of a social housing grant worth ₦1 million. But escalating prices cement up by over 80%, roofing sheets and iron rods nearly double their earlier rates have halted her plans. Her half-built house stands as a silent monument to a dream deferred, while she remains in a temporary shelter at the mercy of seasonal floods and extreme weather (Uzor et al., 2024).

These stories are far from unique. From Rajasthan to Rivers State, from Assam to Zamfara, rural communities across both nations are battling the harsh consequences of inflation in the construction sector. Rising fuel costs, global commodity price shocks, and fragile supply chains have pushed construction materials out of reach for ordinary families (Singh et al., 2021). In rural regions, where infrastructure is limited, the costs are even steeper. Transportation expenses inflate prices further, while local production remains minimal or non-existent. Labor costs too have surged, as workers seek to keep pace with the rising cost of living.

This crisis is not unique to India and Nigeria. In Kenya’s countryside, the cost of iron roofing sheets skyrocketed by more than 30% in 2023, putting hundreds of construction projects behind schedule (Olanrewaju, 2023). In Bangladesh’s coastlines, families continue to reside in cyclone-damaged houses they are unable to repair. Inflation, in all these instances, does not only hit the wallet but takes away security and stability from families.

The fallout is severe. Without proper housing, health risks climb, school attendance drops, and families become more vulnerable to displacement during disasters. Many borrow at exorbitant interest rates from informal lenders just to complete their homes, only to spiral into deeper poverty (Bhattacharjee, 2016). Well-intentioned government programs often fail because they rely on fixed subsidies that do not adjust to rapidly changing market conditions. What looks adequate on paper becomes ineffective in practice (Adebayo & Iweka, 2020).

To reverse this trend, both countries must urgently rethink their housing support systems. Inflation-indexed subsidies and flexible disbursement structures that respond to real-time costs are no longer optional they are essential (Chattopadhyay et al., 2022). Additionally, investments in rural supply chains, promotion of locally available materials like compressed earth blocks or fly ash bricks, and encouragement of affordable, climate-resilient construction methods are vital steps forward.

The voices and struggles of women like Sita and Amina must guide future housing policies. For millions in India, Nigeria, and beyond, a house is not just a place to live it is the first and most important line of defence against poverty. In building homes, we are also building futures.

Inadequate housing directly impacts health from poor sanitation to overcrowding, the risks to physical well-being are immense. Without access to proper shelter, healthcare becomes not just a medical issue but a structural one (Poongavanam et al., 2023). Thus, inflation’s effect on housing also amplifies public health crises.

- The Impact of Inflation on Healthcare in Nigeria and India

Inflation poses a significant challenge to healthcare access and affordability in developing countries. This article compares the effects of inflation on healthcare, specifically medicine prices, in Nigeria and India, highlighting economic drivers, sectoral differences, and policy responses.

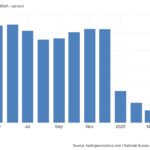

In Nigeria, inflation has sharply increased over recent years, rising from 22.22% in April 2023 to 33.20% in March 2024, far outpacing inflation rates in countries like the UK (Uzor et al., 2024). A recent study analyzing medicine prices in public and private pharmacies in North Central Nigeria found substantial increases across key drug classes between March 2023 and February 2024. Anti-cancer drug prices surged by 75% in public pharmacies, exceeding the 33% increase seen in private ones, reflecting the high demand in specialized hospital settings. Whereas, Antibiotics and Anti-hypertensives increased by 78% and 134% respectively in private pharmacies but only 46% and 24% respectively in public ones (Uzor et al., 2024).

In Nigeria, the public health sector prioritizes affordable access but often suffers stock-outs due to limited funding. Private pharmacies adjust to inflation by raising prices, making medicines less affordable. This widens access gaps and increases out-of-pocket costs, undermining healthcare equity especially among vulnerable populations. (Uzor et al., 2024).

India faces similar inflationary pressures, with healthcare inflation estimated at 20%, driven by the adoption of advanced medical technologies, growing chronic disease burden, and rising demand ((Poongavanam et al., 2023). Although India’s healthcare insurance coverage is broader than Nigeria’s, rising premiums and treatment costs still impact affordability (Poongavanam et al., 2023).

Both countries grapple with challenges from inflation that limit equitable access to essential medicines and healthcare services. Nigeria’s inflation is exacerbated by currency devaluation and import dependence, whereas India’s inflation is influenced by technological advances and evolving healthcare needs (Uzor et al., 2024; Poongavanam et al., 2023).

To mitigate inflation’s impact, Nigeria must expand health insurance coverage, support local drug manufacturing, and improve supply chain management to reduce stock-outs. India’s approach similarly requires policies controlling costs while expanding insurance and investing in healthcare infrastructure (Uzor et al., 2024; Poongavanam et al., 2023).

In conclusion, rising inflation in both Nigeria and India significantly threatens healthcare affordability and access. Addressing these challenges requires strong social protection measures and targeted economic policies that reflect each country’s unique context, ensuring that vulnerable populations are protected and health outcomes are preserved (Uzor et al., 2024; Poongavanam et al., 2023).

Mounting healthcare costs due to inflation force families to divert funds from long-term investments like education. As medical needs become more urgent and expensive, children’s schooling is delayed or discontinued, making it harder for communities to break free from cycles of poverty.

- Impact on Inflation on Education Sector

The impact on inflation has been widespread in every dimension of society. It targets the basic amenities of living. It impacts the education sector in a way that the causal relationship between inflation and school dropout rates can be studied. The case studies of Nigeria and India indicate the similarities in the outcomes of inflation on education in low-income families and rural households. The qualitative and quantitative studies of the causes and impact of inflation present a comprehensive study to understand the patterns of the impact. The social, psychological, economic, and emotional aspects of inflation in the education sector define the wide range of impacts it has. The economic boundaries lead to the differential treatment of children within the family. The intersectionality of gender bias and economic constraints happens to be a promoter of discriminatory practices in society. The Anambra state of Nigeria witnessed a high student dropout rate in the region in the past decade. This can be inevitably interlinked with the food basket inflation in the country. This has led people to resort to money-saving strategies, with reducing investment in education being the foremost escape.

Food importation is acutely relied upon by the country, while domestic challenges, about very low levels of local food production, inadequate infrastructure, and insecurity within the most vital agricultural areas, have alarmingly spiked up food prices(Obibuba, 2024). The food basket inflation has led to the natives prioritising their necessities, with education being at the lowest rung of the ladder of significance. This has been witnessed with a similar pattern in the Indian region. A quantitative methodological survey was conducted in India, spanning across 13 cities, including different tiers and income levels. The causes are the demand-pull factors, cost-push pressures, increased money supply, taxation, and rising production/import costs (Bhattacharjee, 2016). The way forward is presented in the form of policies like inflationary finance and deficit financing for productive use. The top priority must be adhering to the quick-yielding project in the rationing and spreading the word regarding the policy programmes in the rural areas, as the lack of awareness deprives the target mass of the social welfare policies. There has been progress in the path of the upliftment of the rural areas, but a long way to go.

- Impact on the Individual and Society

Beyond the measurable inflation metrics and policy failures lies a deeper, more haunting reality: the quiet breakdown of human potential. At an individual level, villagers face a cruel stagnation: financially, they are drained by surging food and healthcare costs; physically, they are undernourished and medically neglected; structurally, they live in fragile, impermanent homes; and mentally, they are trapped in uncertainty, never knowing whether tomorrow will bring a full meal or safe shelter. Personal development becomes a luxury they cannot afford. Even education, often hailed as a ticket out of poverty, becomes unreachable, either because families cannot afford the costs or because the burden of household survival forces children out of school early.

At the societal level, these micro-crises aggregate into a macro-stagnation. Countries like India and Nigeria continue to struggle with vast, underdeveloped rural populations that remain stuck in post-colonial conditions despite decades of independence and intervention. The cycle of poverty deepens as inflation reinforces inequality, making mobility near impossible. Global perceptions are shaped by these realities: rural underdevelopment becomes a defining trait, casting entire nations as incapable or unworthy of global investment and respect. The failure to address the basic four pillars—food, housing, healthcare, and education—has not only stunted development but has also distorted how the world sees these nations and how these nations see themselves.

Conclusion

In essence, the rural inflation crisis is not fragmented; it is a web, where stress in one domain ripples across the others. The rising cost of food reduces nutritional security and siphons off funds that could support housing or education. The absence of secure shelter leads to health hazards, which in turn generate medical expenses that divert attention from schooling. Each domain—food, housing, healthcare, and education—forms a foundational pillar of human development, and when inflation weakens even one, the rest begin to wobble. For policymakers, this interdependence must not be overlooked. A holistic response is needed, one that recognizes inflation as not just an economic concern but a multi-sectoral threat to rural well-being and human dignity.

References

Adebayo, A. & Iweka, G. (2020). Challenges of public housing delivery in Nigeria.

Bhattacharjee, J. (2017). The impact of inflation on education. International Journal of Applied Research, 3(1), 23–34.

Chattopadhyay, S., et al. (2022). Housing resilience in Indian villages under economic and climate stress.

Gagarawa, A. M., & Mehrotra, M. (n.d.). Impact of inflation on living standard of public primary school teachers in Gagarawa Local Government Area, Jigawa State – Nigeria. Department of Economics, NIMS University, Jaipur.

Mabogunje, A. (2019). Urbanization and housing policy in Nigeria.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019–21 https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR375/FR375.pdf accessed 8 June, 2025.

Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), Consumer Price Index for the month of December 2024 https://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/press_release/CPI_PR_13Jan25.pdf accessed 8 June, 2025.

MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières). (2024). Child malnutrition crisis in Nigeria amid rural violence and soaring food inflation. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/nigeria.

Nairametrics. (2024, June). Nigeria’s imported food inflation jumps to 36.38% in June 2024 on weak naira. Nairametrics.

National Bureau of Statistics Nigeria. (2025). Food inflation in Nigeria increased by 21.26 percent in April 2025 over the same month in the previous year. Nigeria Food Inflation. http://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/.

Obibuba, I. M. (2024). Effect of food inflation on school dropout rate among vulnerable households in Anambra State: Implications for educational psychology. Journal of Education Review, 15(1), 23–32.

Olanrewaju, D. (2023). Inflation-indexed social support systems: A policy review.

Poongavanam, S., Rajan, S., & Kumar, M. (2023). Medical inflation – issues and impact. Chettinad Health City Medical Journal, 12(1), 122–124.

Raihan, S., Ahmed, M. T., Hasan, E., Hasan, M., & Surid, T. F. (2023). Effects of inflation on the livelihoods of poor households in Bangladesh: Findings from SANEM’s Nationwide Household Survey 2023. Dhaka, Bangladesh: SANEM Publications. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375187402

Singh, R., et al. (2021). Inflation and its impact on rural livelihoods in India.

Trading Economics, Nigeria Food Inflation https://tradingeconomics.com/nigeria/food-inflation accessed 8 June, 2025.

Uzor, K. J., Mohammed, A. S., & Eze, C. D. (2024). The impact of inflation on medicine prices in Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal, 49(56).

Welt Hunger Hilfe, Global Hunger Index 2024, [15] https://www.globalhungerindex.org/pdf/en/2024.pdf accessed 8 June, 2025

Individual Contributions

Emmanuel Ogunleye – Contributed to the article by analyzing the impact of inflation on access to healthcare, identifying key trends and correlations that provided insights into the ways economic fluctuations affect healthcare accessibility.

Geetika Pant – Contributed to the article by analyzing the causal relationship between the rising inaccessibility of education and school dropout rates in India and Nigeria, owing to the increasing food basket inflation in contemporary times.

Gannavarpu Rajlakshmi – Contributed to the article by examining the increasing inflation in India and Nigeria, and exploring how it impacts food access and influences the dietary habits of their populations, along with shedding light on the resulting rise in health challenges, especially among women and children.

Seema Samanta – Contributed to the article by analyzing the overall impact of rural inflation on individuals and society. Also interlinking the four fundamental pillars — housing, education, healthcare, and foodproviding a holistic understanding of how inflation affects rural populations and the broader socio-economic landscape of the country.

Chirag Malhotra – Contributed to the article by examining the impact of inflation on rural housing in India and Nigeria, highlighting the socioeconomic consequences through real-life case studies and connecting inflationary pressures with broader structural vulnerabilities in housing access and quality