Understanding Victim Blaming in India

by Sanjna Senthil Kumar

Introduction

Victim blaming is a devaluing act that occurs when the victim of a crime or an accident is held responsible in whole or in part for the crimes that have been committed against them (The Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime, 2009). Victim blaming is a pervasive phenomenon in India that affects a wide range of crimes, including sexual assault, domestic violence, and human trafficking. In India, this act is deeply intertwined with cultural beliefs and systemic biases. Studies have shown that victim blaming is not limited to individual attitudes but is ingrained in institutions and legal structures, which often reinforce the perception that victims are somehow complicit in their misfortunes (Gravelin et al., 2019). This paper emphasises the need for a multifaceted approach to tackle this phenomenon, by understanding its roots in psychological biases, sociocultural norms, and systemic factors.

Psychological Perspectives on Victim Blaming

When we try to understand what exactly influences Victim Blaming, the Just-world hypothesis provides a good baseline. This hypothesis suggests that people have a strong need to believe that the world is a just place where people get what they deserve. When they see someone face victimisation, they often engage in victim blaming to maintain their belief in a just world (Lerner & Miller, 1978). Victim blaming can be seen as a form of scapegoating, where victims are blamed for their own misfortune in order to deflect blame from broader societal issues (Allport, 1954).

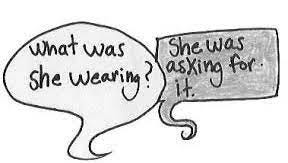

Another relevant theory is the Fundamental Attribution Error, which suggests that people tend to attribute others’ misfortunes to internal factors, such as character flaws, rather than external circumstances. This bias influences people to view victims as somehow responsible for their own suffering (Hafer & Bègue, 2005). Individuals also tend to blame a victim to distance themselves from an unpleasant occurrence and thereby, confirm their own immunity to the risk. They see the victim as someone different from themselves, and by accusing the victim form a sense of reassurance like, “I am different from her, So this would never happen to me.”(Alumni, 2023).

Sociocultural Factors Contributing to Victim Blaming in India

India’s deeply entrenched patriarchal system often places blame on victims of sexual assault and domestic violence. Women are often categorised as victims and males as perpetrators, as seen in the Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) which classifies only women as victims of rape. This further perpetuates patriarchal gender roles, which, when coupled with the existing social norms, inherently put women, and minorities in positions of disadvantage (Hamid, 2021).

Caste and Socioeconomic Marginalisation

Women from socioeconomically marginalized groups are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence in India (Nahvi, 2023). According to an NCRB report, 3,486 Dalit women were raped in 2019 (National Crime Records Bureu, 2019). The perpetrators are mainly men from the upper castes, who argue that they are “putting women in their places” (Nagaraj, 2020). The NCRB data of 2019 shows that 10 Dalit women were raped every day in India. According to another report, over 100 million young Dalit women are subjected to sexual violence at the hands of the so-called Upper Caste men. There is no denying the crippling effects of the caste hierarchy prevalent in Indian society. And among the disadvantaged communities, women suffer the most (Kundu, 2018).

Researchers found that lower-caste Dalit women in northern India are targeted for rape by upper caste men who usually escape justice as survivors bow to pressure to drop their cases (Kundu, 2018). Only 10% of 40 rape cases involving Dalit women and girls in Haryana state ended with the conviction of all those charged, and these involved murder or victims under the age of six (Equality Now & Swabhiman Society, 2018). In almost 60% of cases, the survivor withdrew her case and accepted a “compromise” settlement outside the legal system, usually after unofficial village councils, or Khap Panchayats, coerced the women to abandon their quest for justice (Mashaal, 2018). Survivors are threatened, face violence, their families are ostracised and there is extreme pressure to stay silent (Nagaraj, 2020).

Legal provisions for justice, such as the 1989 Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, are inadequately implemented, and justice remains slippery. Additionally, social stigma and shame surrounding survivors of sexual violence is deeply entrenched in Indian society. Survivors and their families frequently face further victimisation and even social rejection, especially in remote areas. The fear of such stigmatisation results in extremely low reporting rates for assault (Kundu, 2018).

The media’s influence on Victim blaming

Major news networks have a history of using situational information, such as a victim’s alcohol level or the clothes they were wearing, to sway the viewers towards sympathising with the accused rather than the victim. As the primary source of information for most people, the news media plays a vital role in shaping public opinion (Liao, 2023). In the study by Gravelin et al (2024) the tendency for media to overreport stranger rapes and underreport acquaintance rapes was noticed. More victim blaming language was used in reports of acquaintance rape than stranger rape, inturn leading to varied perceptions and greater victim blaming.

Although India has laws like Section 228A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) that protect the identity of sexual assault victims, there is no legislation specifically aimed at preventing victim blaming. For instance, in an analysis of media coverage, it was found that reports of sexual assault involving Dalit women were more likely to include details about the victim’s background, suggesting that caste prejudices still shape public narratives around victimhood and morality (Ramachandran & Whiteley, 2022).

One of the most notable examples of institutional victim blaming in India is the Mathura Rape Case (1979). This case underscores the biases embedded in legal and media narratives, where victims’ behaviours, backgrounds, or social status are scrutinised rather than focusing on the crime itself. Such narratives continue to influence public attitudes, as news outlets frequently mention victims’ actions, clothing, or lifestyle choices, steering public empathy away from victims and toward perpetrators (Minority Rights Group, 2011).

A shift in collective thinking and perceptions is essential to drive long-term and sustainable improvement in India’s fight against Victim Blaming.

The consequences of Victim Blaming

Victim blaming has severe consequences for survivors of sexual violence. It can lead to feelings of shame, guilt, and self-blame, hindering their recovery process. Additionally, it can discourage victims from reporting crimes, leading to underreporting and a lack of justice for perpetrators.

A 2018 report by Mint revealed that 99% of sexual assaults in India go unreported (Kundu, 2018). This alarming statistic highlights the extent to which victim blaming can discourage survivors from seeking help. On average, 60.4% of women don’t recognise their experience as sexual harassment or rape (Ordway, 2021), emphasising the need for more open conversations and education campaigns.

Ways in which Victim Blaming can perpetuate Rape culture

This phenomenon of Victim blaming further adds to the rape culture pervasive in India (Khatana, 2024). Rape culture refers to a societal environment where rape and sexual violence are normalized, often through pervasive attitudes and stereotypes about gender and sexuality (Rape Culture, Victim Blaming, and the Facts | Southern Connecticut State University, n.d.). This normalization appears in everyday acts, including rape jokes, casual sexism, toxic masculinity, victim-blaming, and, at worst, the violent acts themselves. For instance, research highlights how certain forms of media reinforce rape culture by promoting misogynist themes, objectification in popular culture, glamorized violence, and slut-shaming (Kanyemba & College of Humanities, School of Social Sciences, 2018). The language surrounding sexual violence also plays a critical role. When terms like “rape” are used casually, it trivializes the trauma of survivors and, over time, normalizes the idea of rape. Using the word rape in contexts apart from sexual violence and outside the legal definition of rape is insensitive to survivors of assault and abuse and may desensitize individuals to the word and the severity and intensity of the crime it stands for (Pritchard, 2014).

Gender-based violence reporting often reflects problematic cultural values, too, with victim-blaming or “honour” narratives tied to a woman’s sexuality, which can perpetuate societal biases and reinforce a sense of victim responsibility (Yasmin, 2021). Toxic masculinity, characterised by ideas of male dominance, entitlement, and aggression, further fuels this culture by promoting a harmful view of gender roles and justifying male aggression against women (Wikström & Wikström, 2019). Addressing rape culture involves challenging these narratives, altering the media’s approach, and fostering respectful gender perceptions.

Addressing Legal and Institutional Barriers to Combat Victim Blaming in India

To effectively tackle victim blaming in India, several measures must be implemented, supported by empirical evidence and legal frameworks. There were 32,033 cases of sexual violence in India in 2019. Of those, 94.2% of attackers were known to the victim. Also, family members of the victim committed 2,916 cases. Neighbours, employers, or friends committed 10,398 cases. An analysis of the 2015-16 National Family Health Survey highlights significant gaps in the reporting of rape in India, with estimates suggesting that over 99.1% of rape cases go unreported. In the majority of these cases, the accused individuals were the survivors’ husbands, revealing a particularly troubling statistic: women are 17 times more likely to experience sexual violence from their spouses than from others (LiveMint, 2017)

Despite this high prevalence of marital rape, Indian law still does not criminalize it, underscoring the strong influence of patriarchal norms, which obstruct the delivery of justice to victims. Such norms can entrench victim-blaming attitudes and hinder fair treatment for survivors of sexual violence. Addressing these issues requires immediate reforms, including promoting gender equality and ensuring these practices permeate all societal and institutional levels.

Tackling Victim Blaming in India

Establishing stringent laws against marital rape and enforcing existing protections for marginalized groups are crucial. Comparative studies indicate that countries with strong anti-rape laws, including marital rape provisions, have lower rates of victim blaming (Bhat & Ullman, 2013).

Public education campaigns are crucial, mainly educational programs in schools that focus on promoting empathy and understanding towards victims. Providing comprehensive sex education, including modules on consent, healthy relationships, and gender equality, is a key measure in reducing victim-blaming attitudes (Ramachandran & Whiteley, 2022). Educational campaigns that emphasise empathy and address gender stereotypes should be introduced at all educational levels. Comprehensive sex education programs that include discussions on consent, healthy relationships, and gender equality significantly reduce victim-blaming attitudes.

Implementing stricter guidelines to prevent victim-blaming language in news coverage is necessary to reshape public perceptions. Evidence suggests that balanced media portrayals of sexual violence can foster greater empathy for victims and reduce societal stigma (Santoniccolo et al., 2023).

A Feminist Approach to Policy Making

Policymaking related to sexual violence largely operates on outrage adrenaline, pressurised under the scrutiny of public protests, litigations, and international attention. This way of operating under the ‘no action until incident’ manner should be replaced with well-researched and well-planned policies that recognise social and systemic issues as ongoing problems requiring consistent follow-up, and not just big one-time legislations (Nahvi, 2023).

A feminist framework would address gender norms in India, targeting the patriarchal roots of victim blaming. It encourages the active involvement of vulnerable groups, not just as subjects but as contributors to policy solutions. This approach advocates for gender-inclusive policymaking, moving beyond binary gender norms (NGO Sakshi, 1998).

Civil society organisations (CSOs) possess insights into local communities, making them well-suited to address gender-based violence (GBV) awareness and education. Policies should recognize NGOs as key partners in tackling GBV and involve academic research to ensure policies are data-driven (Swabhiman Society, 2022).

The responsibility for rehabilitative and psycho-social support services in India largely falls on civil society organisations (CSOs), which necessitates an institutionalised relationship between the State and civil society to ensure effective coordination and shared responsibility (Ministry of Health & Family Welfare-Government of India, n.d.). A national policy aimed at enhancing collaboration with CSOs would address critical issues such as resource allocation, the nature of partnerships with health services and law enforcement, and institutional support for comprehensive psycho-social care services for survivors of gender-based violence (Palm & UN Women, 2022). These services are essential, particularly considering the societal stigma surrounding topics like sexual abuse, single motherhood, and divorce. These services could include helplines, shelters, legal aid, and long-term psychological support.

One current program, the 181 helpline-integrated One Stop Centres scheme, offers a promising institutional response but requires better resource allocation for adequate personnel training, follow-up mechanisms, and data documentation to operate effectively (Ministry of Women and Child Development et al., 2019). Addressing internalised gender biases among those in judicial, law enforcement, and healthcare roles is also essential, as these biases impact service efficacy and access to justice for survivors. Targeted, role-specific gender-sensitivity training, including GBV case simulations and survivor interaction, is recommended to overcome these challenges (Upadhyay et al., 2023).

Notably, the NGO Sakshi, in collaboration with the Asia-Pacific Judicial Equality Education Programme, introduced a pioneering judicial sensitization program in the late 1990s. This program, aimed at creating a gender-aware judiciary, demonstrated success across South Asia, including Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, by involving judges in discussions with litigants and legal advocates to address gender biases. Apart from this, awareness programs, like the Community Café series by Prajnya Trust (Sahana Iyer & Sahana Iyer, 2022), offer platforms for informal discussions on GBV. Education on gender stereotypes in schools can begin combating gender biases early, as demonstrated by the GEMS (Gender Equity Movement in Schools) program with successful outcomes in multiple countries (International Center for Research on Women).

Conclusion

Victim blaming in India remains a pervasive issue that severely impacts survivors of gender-based violence. This paper emphasises the need for a multifaceted approach to tackle this phenomenon, by understanding its roots in psychological biases, sociocultural norms, and systemic factors. Legal reforms that address patriarchal loopholes, stricter media guidelines to prevent harmful portrayals, and educational initiatives that promote empathy and gender equality are essential steps in addressing and reducing victim-blaming attitudes. Employing a feminist framework that involves civil society and targets both individual and institutional biases can foster a more inclusive and supportive environment. Moving toward this model will help India progress toward a society where victims are respected and supported, rather than blamed and stigmatised.

References

Alumni, I. F. (2023, January 3). Victim blaming – a popular culture in the nation – India fellow. India Fellow. https://indiafellow.org/blog/all-posts/victim-blaming-a-popular-culture-in-the-nation/

Bhat, M., & Ullman, S. E. (2013). Examining Marital Violence in India. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 15(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013496331

Gravelin, C. R., Biernat, M., & Bucher, C. E. (2019). Blaming the victim of acquaintance rape: individual, situational, and sociocultural factors. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02422

Gravelin, C. R., Biernat, M., & Kerl, E. (2024). Assessing the Impact of Media on Blaming the Victim of Acquaintance Rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 48(2), 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/03616843231220960

Hamid, H. B. B. A. (2021). Exploring Victim Blaming Attitudes in Cases of Rape and Sexual Violence: The Relationship with Patriarchy. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 6(11), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.47405/mjssh.v6i11.1147

Kanyemba, R. & College of Humanities, School of Social Sciences. (2018). Normalization of Misogyny: Sexist Humour in a Higher Education Context at Great Zimbabwe University (By University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa). https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/e47bec8f-00a6-40f7-bb7c-eb46180a6b28/content

Khatana, S. (2024, September 3). Infographic: What Is Rape Culture? Feminism in India. https://feminisminindia.com/2020/05/04/infographic-rape-culture/

Kundu, P. B. T. (2018, April 24). 99% cases of sexual assaults go unreported, govt data shows. Mint. https://www.livemint.com/Politics/AV3sIKoEBAGZozALMX8THK/99-cases-of-sexual-assaults-go-unreported-govt-data-shows.html

Liao, C. (2023). Exploring the Influence of Public Perception of Mass Media Usage and Attitudes towards Mass Media News on Altruistic Behavior. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080621

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare-Government of India. (n.d.-a). Role of civil society organisations in facilitating community based monitoring :: National Health Mission. https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=172&lid=246

Ministry of Women and Child Development, Initiative for What works for Women and Girls in the Economy, Institute of Financial Management and Research, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Jagori, & Tata Institute of Social Sciences. (2019a). Rapid Assessment of the Universalization of the 181 Helpline and One Stop Centres. https://iwwage.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Rapid-Assessment-of-181-Helpline-and-One-Stop-Centres.pdf

Minority Rights Group. (2024, March 20). State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2011 – Minority Rights Group. http://minorityrights.org/publications/state-of-the-worlds-minorities-and-indigenous-peoples-2011-july-2011

Nagaraj, A. (2020, November 25). India’s low-caste women raped to keep them “in their place.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/indias-low-caste-women-raped-to-keep-them-in-their-place-idUSKBN28509I/

Nahvi, F. (2023, December 29). The Case for a Feminist Approach to Gender-Based Violence Policymaking in India. orfonline.org. https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-case-for-a-feminist-approach-to-gender-based-violence-policymaking-in-india

Ordway, D. (2021, March 29). Why many sexual assault survivors may not come forward for years. The Journalist’s Resource. https://journalistsresource.org/health/sexual-assault-report-why-research/

Palm, S. & UN Women. (2022a). LEARNING FROM PRACTICE: STRENGTHENING A LEGAL AND POLICY ENVIRONMENT TO PREVENT VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AND GIRLS. In UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women. UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/trust-funds/trust-fund-to-end-violence-against-women

Pritchard, H. (2014). Changing Conversations about Sexual Assault. https://www.gvsu.edu/cms4/asset/903124DF-BD7F-3286-FE3330AA44F994DE/changing_conversations_about_sexual_assault.pdf

Ramachandran, S., & Whiteley, D. (2022, March 11). India’s rape culture: Can education stop sexual violence? THRIVE Project. https://thrivabilitymatters.org/indias-rape-culture-can-education-stop-sexual-violence/

Rape Culture, Victim Blaming, And The Facts | Southern Connecticut State University. (n.d.). https://inside.southernct.edu/sexual-misconduct/facts

Russell, K. J., & Hand, C. J. (2017). Rape myth acceptance, victim blame attribution and Just World Beliefs: A rapid evidence assessment. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 37, 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.10.008

Sahana Iyer, & Sahana Iyer. (2022a, November 23). No longer behind closed doors. The New Indian Express. https://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/chennai/2022/Nov/23/no-longer-behind-closed-doors-2521383.html

Santoniccolo, F., Trombetta, T., Paradiso, M. N., & Rollè, L. (2023a). Gender and Media Representations: A Review of the Literature on Gender Stereotypes, Objectification and Sexualization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105770

The Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime. (2009). Victim blaming. https://crcvc.ca/docs/victim_blaming.pdf

THE PRAJNYA TRUST, & Rajagopalan, S. (n.d.). Annual Report 2012-2013. https://prajnya.in/storage/app/media/ar1213.pdf

Upadhyay, A. K., Khandelwal, K., Iyengar, J., & Panda, G. (2023a). Role of gender sensitisation training in combating gender-based bullying, inequality, and violence. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2266615

Wikström, M. C. & Wikström. (2019a). Gendered Bodies and Power Dynamics: The Relation between Toxic Masculinity and Sexual Harassment. In Granite Journal (Vol. 3, Issue 2, pp. 28–33) [Journal-article]. https://www.abdn.ac.uk/pgrs/documents/Granite%20Gendered%20Bodies%20and%20Power%20Dynamics%20The%20Relation%20between%20Toxic%20Masculinity%20and%20Sexual%20Harassment,%20Wikstrom,%20pp%2028-33.pdf

Yasmin, M. (2021a). Asymmetrical gendered crime reporting and its influence on readers: A case study of Pakistani English newspapers. Heliyon, 7(8), e07862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07862